Gold Trumps Platinum for Chemotherapy Compounds

Gold-based drugs can slow tumour growth in animals by 82% and target cancers more selectively than standard chemotherapy drugs, according to new research out of RMIT University. The study published in the European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry reveals a new gold-based compound that’s 27 times more potent against cervical cancer cells in the lab than standard chemotherapy drug cisplatin.

It was also 3.5 times more effective against prostate cancer and 7.5 times more effective against fibrosarcoma cells in the lab. In mice studies, the gold compound reduced cervical cancer tumour growth by 82%, compared to cisplatin’s 29%.

Project lead at RMIT, Distinguished Professor Suresh Bhargava AM, said it marked a promising step towards alternatives to platinum-based cancer drugs.

“These newly synthesised compounds demonstrate remarkable anticancer potential, outperforming current treatments in a number of significant aspects including their selectivity in targeting cancer cells,” said Bhargava, Director of RMIT’s Centre for Advanced Materials and Industrial Chemistry. “While human trials are still a way off, we are really encouraged by these results.”

The gold-based compound is patented and ready for further development towards potential clinical application.

Gold: the noblest element

Gold is famously known as the noblest of all metals because it has little or no reaction when encountering other substances. However, the gold compound used in this study is a chemically tailored form known as Gold(I), designed to be highly reactive and biologically active.

This chemically reactive form was then tailored to interact with an enzyme abundant in cancer cells, known as thioredoxin reductase.

By blocking this protein’s activity, the gold compound effectively shuts down cancer cells before they can multiply or develop drug resistance.

Project co-lead at RMIT, Distinguished Professor Magdalena Plebanski, said along with this ability to block protein activity, the compound also had another weapon in its anti-cancer arsenal.

In zebrafish studies, it was shown to stop the formation of new blood vessels that tumours need in order to grow.

This was the first time one of the team’s various gold compounds had shown this effect, known as anti-angiogenesis.

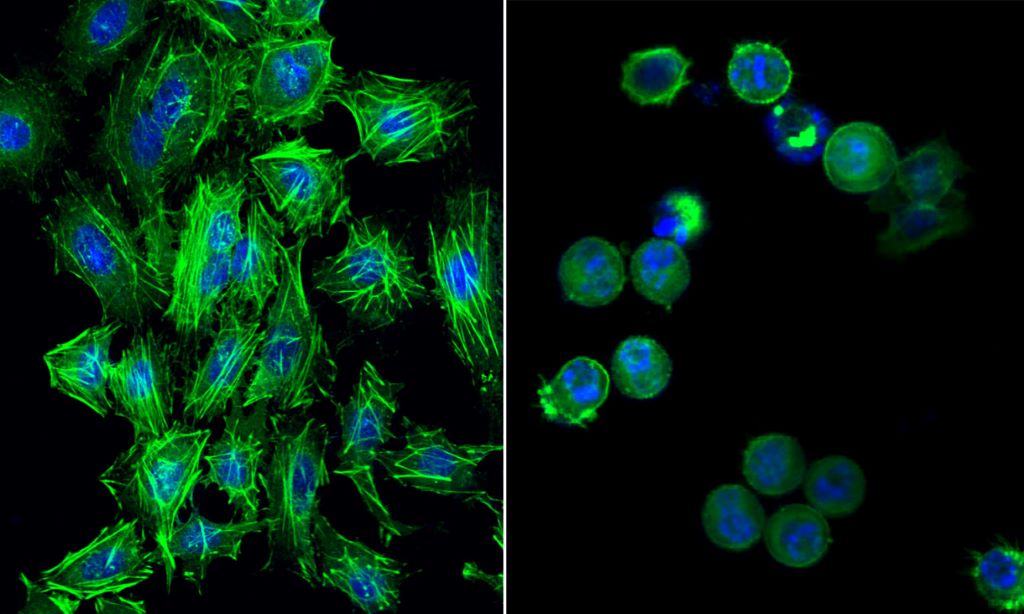

The drug’s effectiveness at using these two attacks simultaneously was demonstrated against a range of cancer cells.

This included ovarian cancer cells, which are known to develop resistance to cisplatin treatment in many cases.

“Drug resistance is a significant challenge in cancer therapy,” said Plebanski, who heads RMIT’s Cancer, Ageing, and Vaccines Laboratory.

“Seeing our gold compound have such strong efficacy against tough-to-treat ovarian cancer cells is an important step toward addressing recurrent cancers and metastases.”

Gold has been a cornerstone of Indian Ayurvedic treatments for centuries, celebrated for its healing properties. Today, gold-based cancer treatments are gaining global traction, with advancements such as the repurposing of the anti-arthritic drug auranofin, now showing promise in clinical trials for oncology.

“We know that gold is readily accepted by the human body, and we know it has been used for thousands of years in treating various conditions,” Bhargava said.

“Essentially, gold has been market tested, but not scientifically validated.

“Our work is helping both provide the evidence base that’s missing, as well as delivering new families of molecules that are tailor-made to amplify the natural healing properties of gold,” he said.

Bhargava said this highly targeted approach minimises the toxic side effects seen with the platinum-based cisplatin, which targets DNA and damages both healthy and cancerous cells.

“Their selectivity in targeting cancer cells, combined with reduced systemic toxicity, points to a future where treatments are more effective and far less harmful,” Bhargava said.

This specific form of gold was also shown to be more stable than those used in earlier studies, allowing the compound to remain intact while reaching the tumour site.