Brain Ages at Different Paces According to Social and Physical Environments

An international study employing advanced measurements of brain ageing on a wide range of participants found that people from more disadvantaged countries and backgrounds had older biological ages for their brains compared to chronological ages. The results are published in Nature Medicine.

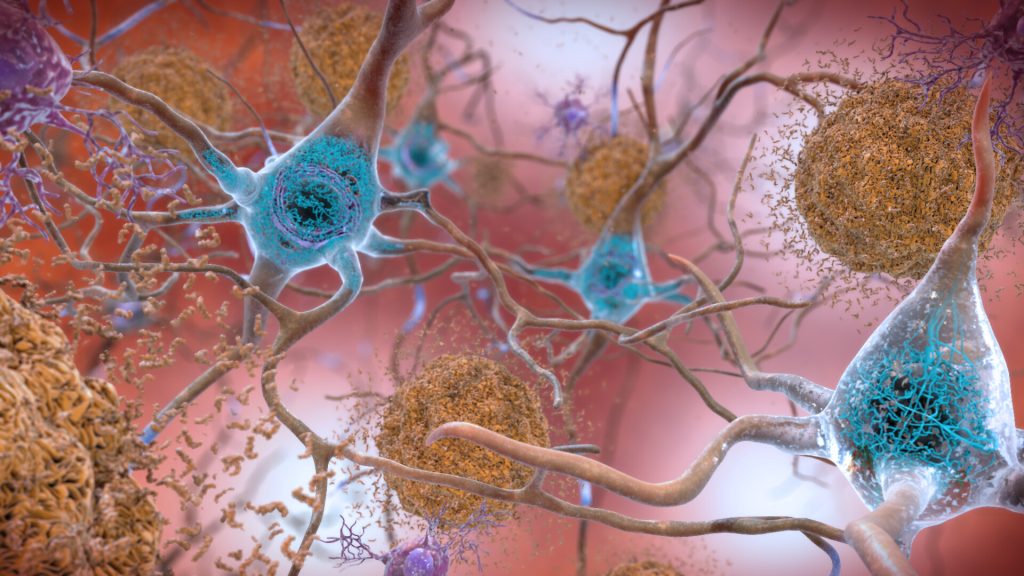

The pace at which the brain ages can vary significantly among individuals. This difference between biological and chronological ages may be affected by environmental factors like pollution and social factors like income or health inequalities, especially in older people and those with dementia. Until now, it was unclear how these combined factors could either accelerate or delay brain ageing across diverse geographical populations.

The study used advanced brain clocks based on deep learning of brain networks, involved a diverse dataset of 5306 participants from 15 countries. By analysing data from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG), the researchers quantified brain age gaps in healthy individuals and those with neurodegenerative conditions such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease, and frontotemporal lobe degeneration (FTLD).

Participants with a diagnosis of dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, exhibited the most critical brain age gaps. The research also highlighted sex differences in brain ageing, with women in Latin American and Caribbean countries showing greater brain age gaps, particularly in those with Alzheimer’s disease. These differences were linked to biological sex and gender disparities in health and social conditions. Variations in signal quality, demographics, or acquisition methods did not explain the results. These findings underscore the role of environmental and social factors in brain health disparities.

The findings of this study have profound implications for neuroscience and brain health, particularly in understanding the interaction between macro factors (exposome) and the mechanisms that underlie brain ageing across diverse populations in healthy ageing and dementia. The study’s approach, which integrates multiple dimensions of diversity into brain health research, offers a new framework for personalised medicine. This framework could be crucial for identifying individuals at risk of neurodegenerative diseases and developing targeted interventions to mitigate these risks. Moreover, the study’s results highlight the importance of considering the biological embedding of environmental and social factors in public health policies. Policymakers can reduce brain age gaps and promote healthier ageing across populations by addressing issues such as socioeconomic inequality and environmental pollution.

Source: University of Surrey