Positive Life Experiences Boost Brain Mitochondria

Having more positive experiences in life is associated with lower odds of developing brain disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, slower cognitive decline with age, and even a longer life. But how feelings and experiences are translated into physical changes that protect or harm the brain is still unclear.

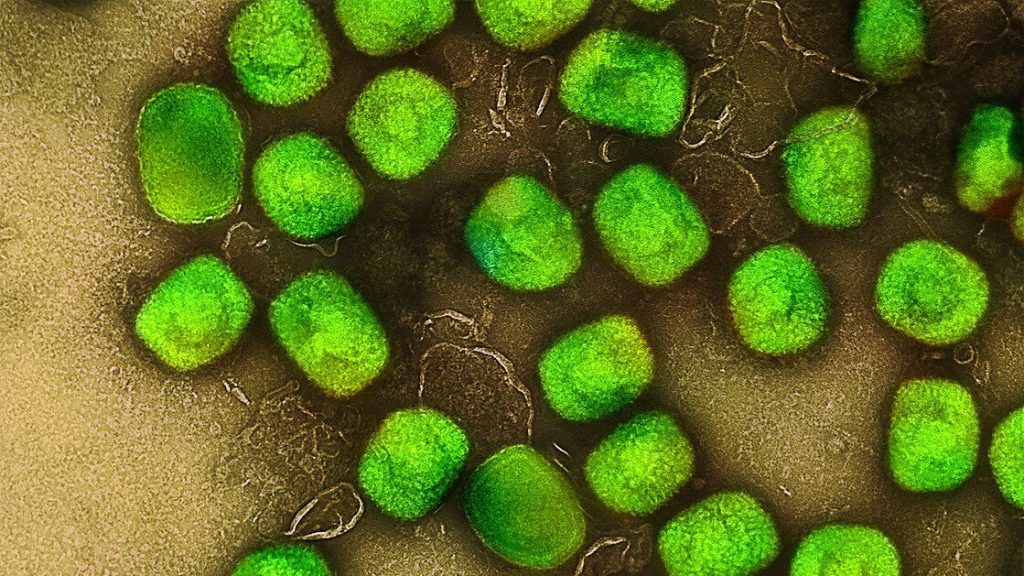

Now, a study from Columbia researchers suggests that the brain’s mitochondria may play a fundamental part. The new study shows that the molecular machinery used by mitochondria to transform energy is boosted in older adults who experienced less psychological stress during their lives compared with individuals who had more negative experiences.

“We’re showing that older individuals’ state of mind is linked to the biology of their brain mitochondria, which is the first time that subjective psychosocial experiences have been related to brain biology,” says Caroline Trumpff, assistant professor of medical psychology, who led the research with Martin Picard, associate professor of behavioural medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and in the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center.

“We think that the mitochondria in the brain are like antennae, picking up molecular and hormonal signals and transmitting information to the cell nucleus, changing the life course of each cell,” says Picard. “And if mitochondria can change cell behaviour, they can change the biology of the brain, the mind, and the whole person.”

Study details

The new research used data collected by two extensive studies of nearly 450 older adults in the United States. Each study collected detailed psychosocial information from the participants for two decades during their lives. Study participants donated their brains after death for further analysis, which provided data on the state of the participants’ brain cells.

Trumpff created indices that converted patients’ reports of positive and negative psychosocial factors into a single score of overall psychosocial experience. She also scored each participant on seven domains that represent distinct genetic networks active in mitochondria.

“The use of multivariate mitotype indices is an important innovation because we could more easily interpret the biological state of the mitochondria with networks of related genes than an analysis of thousands of individual genes,” Picard says.

Study results

The results showed that one mitochondrial domain – which assessed the organelle’s energy transformation machinery – was associated with psychosocial scores.

“Greater well-being was linked to greater abundance of proteins in mitochondria needed to transform energy, whereas negative mood was linked to lower protein content,” Trumpff says. “This may be why chronic psychological stress and negative experiences are bad for the brain, because they damage or impair mitochondrial energy transformation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for high-level cognitive tasks.”

The researchers also analysed mitochondria in specific cell types in the brain and found that the associations between mitochondria and psychosocial factors were driven not by the brain’s neurons, but its glia cells, which may be playing more than their traditionally assumed “supportive” roles.

“This piece of the study, made possible by our collaboration with the Columbia Center for Translational and Computational Neuroimmunology, is what I think makes it particularly significant,” Picard says. “To ask questions at this level of cellular resolution in the brain is unprecedented in the mitochondrial field.

“Neurons have been the focus of neuroscience, but we’re waking up to the fact that other cells in the brain may be driving disease.”

Do mitochondria change mood, or does mood change mitochondria?

Though the current study cannot determine if the participant’s psychosocial experiences altered their brain mitochondria or if innate or acquired mitochondrial states contributed to those experiences, other studies suggest that the relationship between mitochondria and mood works both ways.

In animal studies, the evidence is very strong, Picard says, that chronic stress affects mitochondrial energy transformation. And in people, a recent study conducted by Picard and collaborator Elissa Epel at UCSF found the first evidence that mood may affect mitochondria in humans: In that study, positive mood predicted greater mitochondrial energy production in the participants’ blood cells on subsequent days, but mitochondrial activity did not predict mood on subsequent days.

A growing body of work in animals and humans also indicates that mitochondria themselves can alter behaviour.

“It’s possible that these mechanisms reinforce one another,” Trumpff says. “Chronic stress could alter an individual’s mitochondrial biology in ways that subsequently affects their perception of social events, creating more stress. The emerging picture in the literature is that all these pathways are interactive.”

Next steps

Though the brain’s energy transformation machinery was greater in participants with higher psychosocial scores, the researchers do not yet know if that leads to greater energy transformation. Trumpff and Picard are currently doing those studies with hundreds of brains from the same cohorts of participants.

The team is also exploring a way to measure the brain’s mitochondrial health, which could be used in doctors’ offices in the future.

“Mitochondria are the source of health and life, but we don’t have ways to quantify health, only disease,” Picard says. “We need a science of health. We need tests that show how healthy and resilient someone is.

“This would be valuable clinically to monitor changes in health before the appearance of disease, and it could transform medical research by giving scientists something to target other than decades of accumulated protein deposits or other forms of long-term damage.”