Singing Repairs the Language Network of the Brain after Stroke

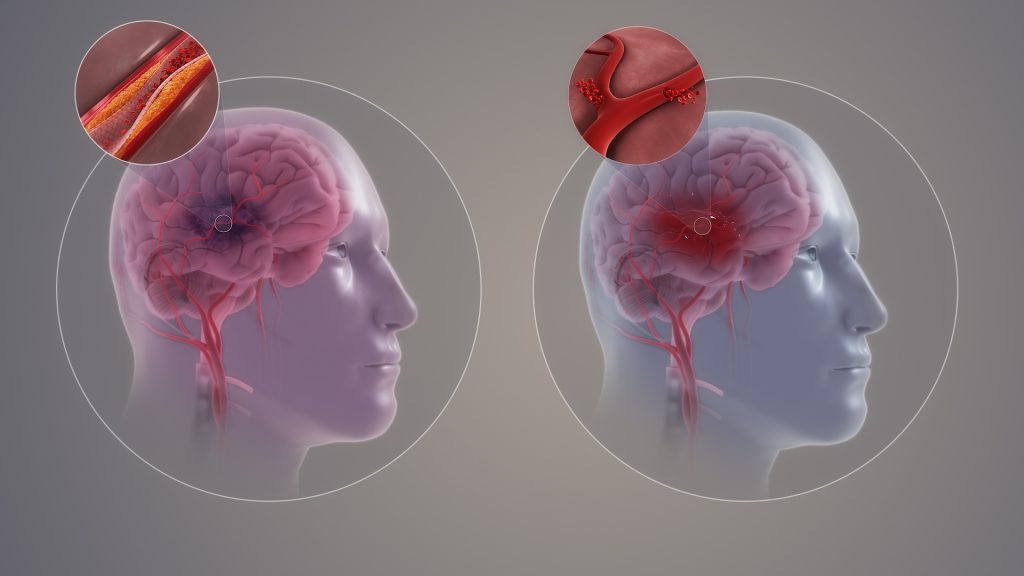

Cerebrovascular accidents, or strokes, are the most common cause of aphasia, a speech disorder of cerebral origin. People with aphasia have a reduced ability to understand or produce speech or written language. An estimated 40% of people who have had a stroke have aphasia. As many as half of them experience aphasia symptoms even a year after the original attack.

Researchers at the University of Helsinki previously found that sung music helps in the language recovery of patients affected by strokes. Now, the researchers have uncovered the reason for the rehabilitative effect of singing. The recently completed study was published in the eNeuro journal.

According to the findings, singing, as it were, repairs the structural language network of the brain. The language network processes language and speech in the brain, which has been damaged.

“For the first time, our findings demonstrate that the rehabilitation of patients with aphasia through singing is based on neuroplasticity changes, that is, the plasticity of the brain,” says University Researcher Aleksi Sihvonen from the University of Helsinki.

Singing improves language network pathways

The language network encompasses the cortical regions of the brain involved in the processing of language and speech, as well as the white matter tracts that convey information between the different end points of the cortex.

According to the study results, singing increased the volume of grey matter in the language regions of the left frontal lobe and improved tract connectivity especially in the language network of the left hemisphere, but also in the right hemisphere.

“These positive changes were associated with patients’ improved speech production,” Sihvonen says.

A total of 54 aphasia patients participated in the study, of whom 28 underwent MRI scans at the beginning and end of the study. The researchers investigated the rehabilitative effect of singing with the help of choir singing, music therapy and singing exercises at home.

Singing is a cost-effective treatment

Aphasia has a wide-ranging effect on the functional capacity and quality of life of affected individuals and easily leads to social isolation.

According to Sihvonen, singing can be seen as a cost-effective addition to conventional forms of rehabilitation, or as rehabilitation for mild speech disorders in cases where access to other types of rehabilitation is limited.

“Patients can also sing with their family members, and singing can be organised in healthcare units as a group-based, cost-efficient rehabilitation,” Sihvonen says.

Source: University of Helsinki