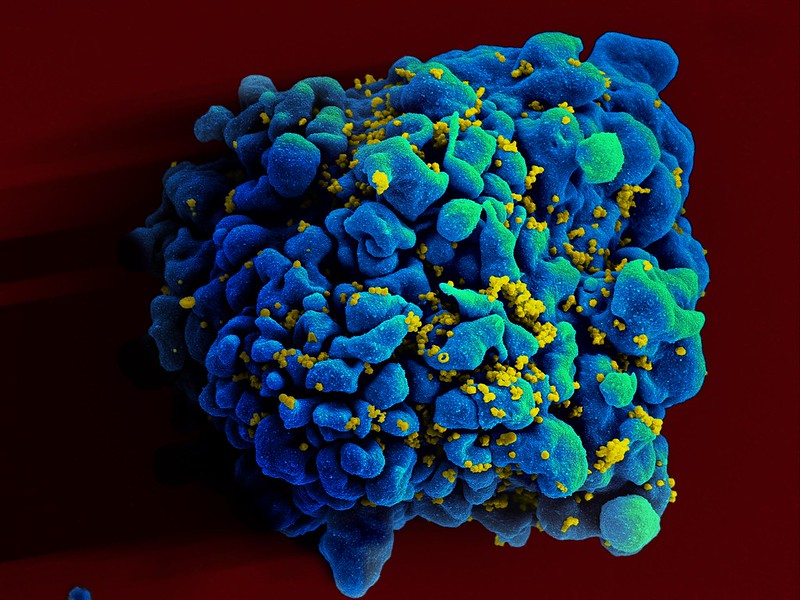

Australian researchers have discovered a previously unknown rogue immune cell that can cause poor antibody responses in chronic viral infections. The finding, published in the journal, Immunity, may lead to earlier intervention and possibly prevention of some types of viral infections such as HIV or hepatitis.

One of the remaining mysteries of the human immune system is why ‘memory’ B cells often only have a weak capacity to protect us from persistent infections.

In an answer to this, researchers from the Monash University Biomedicine Discovery Institute have now discovered that chronic viral infection induces a previously unknown immune B memory cell that does not produce high levels of antibodies.

Importantly the research team, led by Professor Kim Good-Jacobson and Dr Lucy Cooper, also determined the most effective time during the immune response for therapeutics such as anti-viral and anti-cancer drugs to better boost immune memory cell development.

“What we discovered was a previously unknown cell that is produced by chronic viral infection. We also determined that early intervention with therapeutics was the most effective to stop this type of memory cell being formed, whereas late intervention could not,” Professor Good-Jacobson said.

According to Dr Cooper, chronic viral infections have been known to alter our ability to form effective long-term protective antibody responses, but how that happens is unknown.

“In the future, this research may result in new therapeutic targets, with the aim to reduce the devastating effect of chronic infectious diseases on global health, specifically those that are not currently preventable by vaccines,” she said.

“Revealing this new immune memory cell type, and what genes it expresses, allows us to determine how we can target it therapeutically and whether that will lead to better antibody responses.”

The research team are also looking to see whether this population is a feature of long COVID, which results in some people having a reduced capacity to fight off the symptoms of COVID infection long after the virus has dissipated.

Source: Monash University