New Study Links Placental Oxygen Levels to Foetal Brain Development

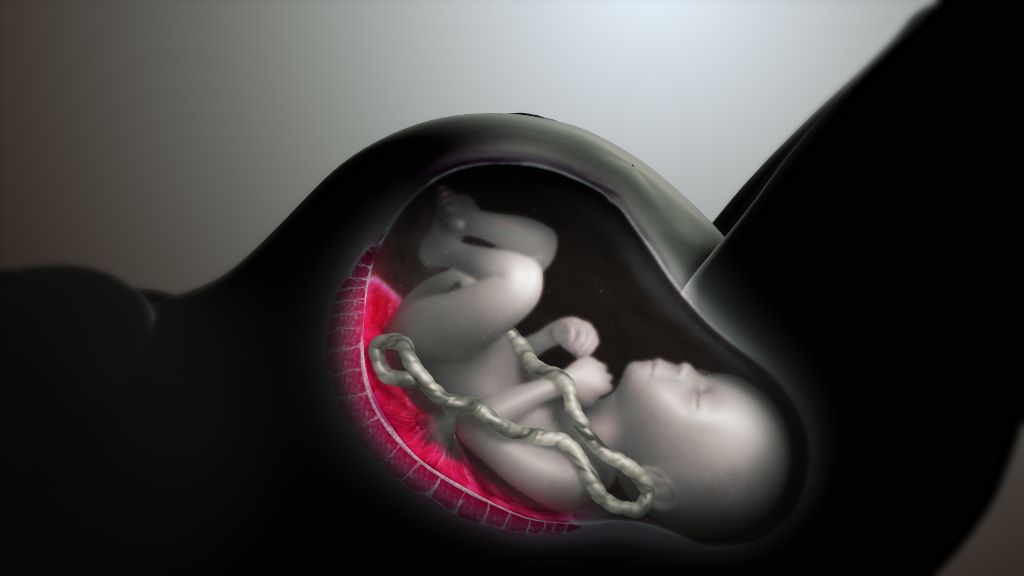

A new study published in JAMA Network Open shows oxygenation levels in the placenta, formed during the last three months of foetal development, are an important predictor of cortical growth and is likely a predictor of childhood cognition and behaviour.

“Many factors can disrupt healthy brain development in utero, and this study demonstrates the placenta is a crucial mediator between maternal health and foetal brain health,” said Emma Duerden, Canada Research Chair in Neuroscience & Learning Disorders at Western University, Lawson Health Research Institute scientist and senior author of the study.

The connection between placental health and childhood cognition was demonstrated in previous research using ultrasound, but for this study, Duerden, research scientist Emily Nichols and an interdisciplinary team of Western and Lawson researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a far superior and more holistic imaging technique. This novel approach to imaging placental growth allows researchers to study neurodevelopmental disorders very early on in life, which could lead to the development of therapies and treatments.

“While ultrasound provides some measure of placental function, it is imprecise and prone to error, so MRI is just a bit more specific and precise,” said Nichols, lead author of the study. “You wouldn’t use MRI necessarily to diagnose placental growth restriction, you would use ultrasound, but MRI gives us a much better way to understand the mechanisms of the placenta and how placental function is affecting the foetal brain.”

The study was led by Duerden and Nichols and co-authored by researchers from the Faculty of Education, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western Engineering and Lawson Health Research Institute.

The placenta, an organ that develops in the uterus during pregnancy, is the main conduit for oxygenation and nutrients to a fetus, and a vital endocrine organ during pregnancy.

“Anything a foetus needs to grow and thrive is mostly delivered through the placenta so if there is anything wrong with the placenta, the foetus might not be receiving the nutrients or the levels of oxygenation it needs to thrive,” said Nichols.

Poor nutrition, smoking, cocaine use, chronic hypertension, anaemia, and diabetes may result in foetal growth restriction and may cause problems for the development of the placenta. Foetal growth restriction is relatively common and happens in about six per cent of all pregnancies and globally impacts 30 million pregnancies each year.

“There can be many issues related to the healthy development of the placenta,” said Duerden. “If it does not develop properly, the foetal brain may not get enough oxygen and nutrients, which may affect childhood cognition and behaviour.”

Impact, affect and change

The study revealed that a healthy placenta in the third trimester particularly impacts the cortex and the prefrontal cortex, regions of the child’s brain that are important for learning and memory.

“An unhealthy placenta can place babies at risk for later life learning difficulties, or even something more serious, like a neurodevelopmental disorder,” said Duerden. “This research can open a lot of doors as we still don’t really understand everything there is to know about the placenta. We are just scratching the surface.”

The study, funded by grants from Brain Canada, The Children’s Health Research Institute, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, BrainsCAN and the Molly Towell Perinatal Research Foundation, is also an important first step in biomarking the impact of oxygenation levels in the placenta and considering changes for expectant mothers to deal with less-than-ideal placental conditions.

While oxygenation in the placenta in the third trimester predicts foetal cortical growth (development of the outermost layer of the brain – the cerebral cortex), results of the study indicate it may not affect subcortical maturation, or the deep grey and white matter structures of the brain.

Subcortical structures in the brain, responsible for children’s temperament or motor functions such as the amygdala and basal ganglia, may be more vulnerable to factors affecting the placenta in the second trimester.

“We now have a better understanding of how the placenta affects the cortex. With this basic knowledge, we now have an idea of how these two things are related and we can identify or benchmark healthy levels that lead to brain cortical growth,” said Nichols. “The subcortical regions of the brain appear to be unaffected by placental growth, at least in the healthy samples from our study.”

Duerden, Nichols, and the team scanned pregnant women twice (during their third trimester) for the study at Western’s Translational Imaging Research Facility.

“This is one of the few datasets in the world where there are two scans collected in utero during the third trimester. There are not many groups in the world doing foetal MRI, so it is a super-rich data set that allows us to look at growth over time,” said Duerden. “Western is probably one of the few places where we can do the research because we have the expertise and the facilities to do it.”

Source: University of Western Ontario