Treating Tuberculosis when Antibiotics Become Ineffective

An international research team has found a number of substances with a dual effect against tuberculosis (TB): They make the bacteria causing the disease less pathogenic for human immune cells whilst boosting the activity of conventional antibiotics. They published their findings in the journal Cell Chemical Biology.

Infectious disease specialist Dr Jan Rybniker and colleagues have identified new, antibiotic molecules that target Mycobacterium tuberculosis and make it less pathogenic for humans.

In addition, some of the discovered substances may allow for a renewed treatment of tuberculosis with available medications – including strains of the bacterium that have already developed drug resistance.

Although treatable with antibiotics, it still ranks among the infectious diseases that claim the most lives worldwide: According to the World Health Organization (WHO), only COVID was deadlier than TB in 2022. The disease also caused almost twice as many deaths as HIV/AIDS. More than 10 million people continue to contract TB every year, mainly due to insufficient access to medical treatment in many countries.

Limited targets

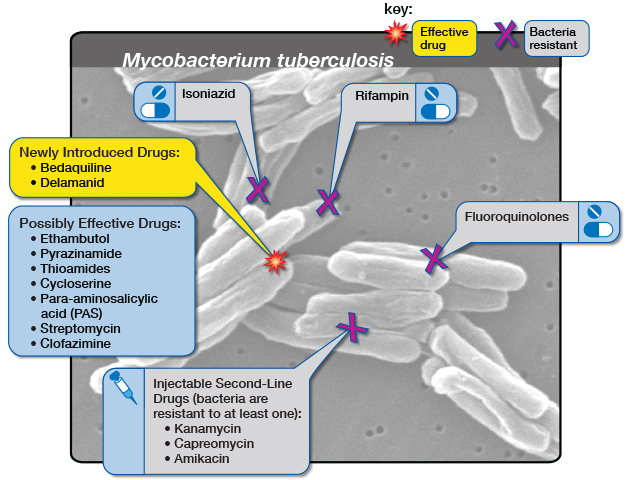

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis is emerging especially in eastern Europe and Asia. That is of particular concern to researchers because like all bacteria that infect humans, Mycobacterium tuberculosis possesses only a limited number of targets for conventional antibiotics.

That makes it increasingly difficult to discover new antibiotic substances in research laboratories.

Working together with colleagues from the Institute Pasteur in Lille, France, and the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), the researchers at University Hospital Cologne have now identified an alternative treatment strategy for the bacterium.

The team utilized host-cell-based high-throughput methods to test the ability of molecules to stem the multiplication of bacteria in human immune cells: From a total of 10,000 molecules, this procedure allowed them to isolate a handful whose properties they scrutinized more closely in the course of the study.

Two-pronged attack

Ultimately, the researchers identified virulence blockers that utilise target structures that are fundamentally distinct from those targeted by classical antibiotics.

“These molecules probably lead to significantly less selective pressure on the bacterium, and thus to less resistance,” said Jan Rybniker, who heads the Translational Research Unit for Infectious Diseases at the Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne (CMMC) and initiated the study.

In deciphering the exact mechanism of action, the researchers also discovered that some of the newly identified chemical substances are dual-active molecules.

Thus, they not only attack the pathogen’s virulence factors, but also enhance the activity of monooxygenases — enzymes required for the activation of the conventional antibiotic ethionamide.

Ethionamide is a drug that has been used for many decades to treat TB. It is a so-called prodrug, a substance that needs to be enzymatically activated in the bacterium to kill it. Therefore, the discovered molecules act as prodrug boosters, providing another alternative approach to the development of conventional antibiotics.

In cooperation with the research team led by Professor Alain Baulard at Lille, the precise molecular mechanism of this booster effect was deciphered.

Thus, in combination with these new active substances, drugs that are already in use against tuberculosis might continue to be employed effectively in the future.

The discovery offers several attractive starting points for the development of novel and urgently needed agents against tuberculosis.

“Moreover, our work is an interesting example of the diversity of pharmacologically active substances. The activity spectrum of these molecules can be modified by the smallest chemical modifications,” Rybniker added.

However, according to the scientists it is still a long way to the application of the findings in humans, requiring numerous adjustments of the substances in the laboratory.

Source: University of Cologne