It has long been known that people with diabetes are at a substantially increased risk of developing severe lung disease if they become infected with viruses such as influenza, as well as other pathogens. When the COVID-19 pandemic started in early 2020, it became even more important to understand this mysterious phenomenon. It became clear that people with diabetes were at a significantly higher risk of coming down with severe, even fatal, lung disease after developing severe COVID, but no one understood why. In fact, some 35% of the pandemic’s COVID mortalities had diabetes.

Now, research conducted at the Weizmann Institute of Science and published in Nature has revealed how, in diabetics, high levels of blood sugar disrupt the function of key cell subsets in the lungs that regulate the immune response. It also identifies a potential strategy for reversing this susceptibility and saving lives.

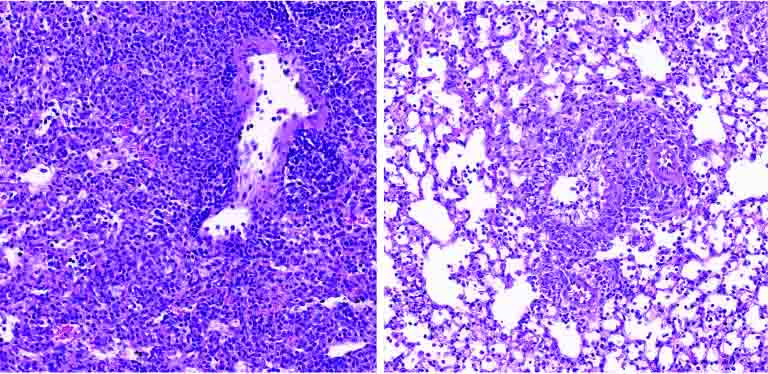

Prof. Eran Elinav‘s team in his lab at Weizmann, headed by Drs. Samuel Nobs, Aleksandra Kolodziejczyk and Suhaib K. Abdeen, subjected multiple mouse models of types 1 and 2 diabetes to a variety of viral lung infections. Just as in diabetic humans, in all these models the diabetic mice developed a severe, fatal lung infection following exposure to lung pathogens such as influenza. The immune reaction, which in nondiabetics eliminates the infection and drives tissue healing, was severely impaired in the diabetic mice, leading to uncontrolled infection, lung damage and eventual death.

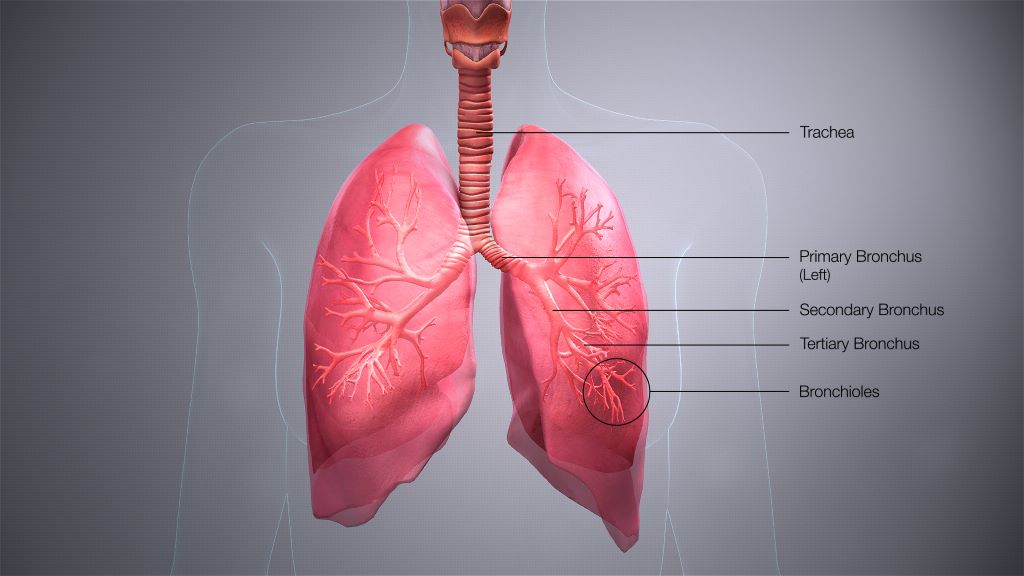

Next, to decode the basis of this heightened risk, the team performed an evaluation of gene expression on the level of individual cells, in more than 150 000 single lung cells of infected diabetic and nondiabetic mice. The researchers also performed an extensive array of experiments involving immune and metabolic mechanisms, as well as an in-depth assessment of immune cell gene expression in infected diabetic mice. In the diabetic mice they identified a dysfunction of certain lung dendritic cells, the immune cells that orchestrate a targeted immune response against pathogenic infection. “High blood sugar levels severely disrupt certain subsets of dendritic cells in the lung, preventing these gatekeepers from sending the molecular messages that activate the critically important immune response,” says Nobs, postdoctoral fellow and study first author. “As a result, the infection rages on, uncontrolled.”

Next, they explored ways to prevent the harmful effects of hyperglycaemia in lung dendritic cells, as a means of lowering the infection’s risk in diabetic animals. Indeed, tight control of glycaemic levels by insulin supplementation prompted the dendritic cells to regain their capacity to generate a protective immune response that could prevent the cascade of events leading to a severe, life-threatening viral lung infection. Alternatively, administration of small molecules reversing the sugar-induced regulatory impairment corrected the dendritic cells’ dysfunction and enabled them to generate a protective immune response despite the presence of hyperglycaemia.

“Correcting blood sugar levels, or using drugs to reverse the gene regulatory impairment induced by high sugar, enabled our team to get the dendritic cells’ function back to normal,” says Abdeen, a senior intern who co-supervised the study. “This was very exciting because it means that it might be possible to block diabetes-induced susceptibility to viral lung infections and their devastating consequences.”

With over 500 million people around the world affected by diabetes, and with diabetes incidence expected to rise over the next decades, the new research has significant, promising clinical implications.

“Our findings provide, for the first time, an explanation as to why diabetics are more susceptible to respiratory infection,” Elinav says. “Controlling sugar levels may make it possible to reduce this pronounced diabetes-associated risk. In diabetic patients whose sugar levels are not easily normalized, small molecule drugs may correct the gene alterations caused by high sugar levels, potentially alleviating or even preventing severe lung infection. Local administration of such treatments by inhalation may minimize adverse effects while enhancing effectiveness, and merits future human clinical testing.”

Source: Weizmann Institute of Science