By Jesse Copelyn for Spotlight

A small study published in September found that some ceramic plates and bowls bought from South African chain stores are coated in glaze that contains lead, a toxic heavy metal which can damage multiple organs when consumed. The paper comes in the wake of research that finds that due to its harmful effects on the cardiovascular system, lead exposure is linked to the deaths of somewhere between 2.3 and 8.2 million people a year worldwide (these findings are dissected in part one of this Spotlight special series on lead poisoning).

It is estimated that about 7.8 million children in South Africa (aged 0-14) have lead poisoning, which is about 53% of all young people in that age-range. This means that they have more than five micrograms of lead per 100mL of blood, the clinical threshold for lead poisoning set by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases. Lead increases the risk of health problems at any level, however if a healthcare worker finds that a patient exceeds this threshold then this indicates that the problem is severe enough that they should notify the health department.

But why are children in the country exposed to so much lead?

Scientists from the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) have found several sources over the last two decades. These include lead-based paints (which can chip and generate lead dust which people breathe in), certain traditional ayurvedic medicines that contain lead, fishing sinkers (which are sometimes melted down, producing toxic fumes), lead ammunition (which can generate lead dust when fired, and may contaminate hunted game meat), as well as gold mining waste facilities, which can contaminate the surrounding soil.

The recent paper on ceramics adds to a growing body of evidence that cookware and crockery also likely play a role.

Toxic pottery

Research for the new paper was conducted in 2018, when SAMRC scientists purchased 44 randomly selected plates and bowls from six large retail chain stores in Johannesburg. After testing the glaze, they found that almost 60% of the items contained more than the maximum amount of lead recommended by the United Nations – which is 0.009% of total content. Indeed, the average item contained about 47 times this amount.

Glaze is a liquid coating that is applied to ceramic to make it shinier and more durable. Once it’s coated, the ceramic is fired, leaving it with a glossy sheen. Lead is often used in these glazes to add extra colour and increase water-resistance, but if the ceramic isn’t heated at a high enough temperature then the glaze won’t completely solidify. In the case of ceramic crockery, this means that lead may run off into food or water prepared in these dishes, particularly if they are used for cooking or simply holding acidic foods.

Indeed, this is precisely what has happened throughout parts of Mexico. Research in that country finds that children have higher amounts of lead in their blood if they live in households where food is prepared in lead-glazed pottery (a result which researchers have found repeatedly). Recently, health inspectors in the US linked cases of lead poisoning to the use of ceramic cookware bought in Mexico. After the affected individuals stopped using the ceramics, their blood-lead levels went down.

In order to test whether lead is leaching off the South African ceramics, the SAMRC researchers left an acidic solution in the plates and bowls. When they returned 24 hours later, lead was found to have run off one of the 44 items.

Angela Mathee, the head of the SAMRC’s Environment and Health Research Unit and the paper’s lead author, says that while this is comforting, the results may be deceiving: “our speculative concern is that particularly for people who are poor and keep their ceramic ware for a very long time, that with knocks and cracks and wear and tear over the years, it’s possible that the product could start leaching – even if it wasn’t at the time of purchase. Though that is untested”.

A second caveat is that of the 44 bowls and plates, only one was originally made in South Africa, and it’s this item that released lead.

Additionally, even if lead-based ceramics don’t leach, the production of these items may still cause harm. For instance, a study in Brazil found that children who simply lived near artisanal pottery workshops were more likely to have high amounts of lead in their blood. Caregivers of these children did not report having any lead-glazed ceramics or being involved in pottery making. Thus, researchers suspect that children were simply breathing in lead dust generated by the nearby potters.

Lead leaching from cooking pots

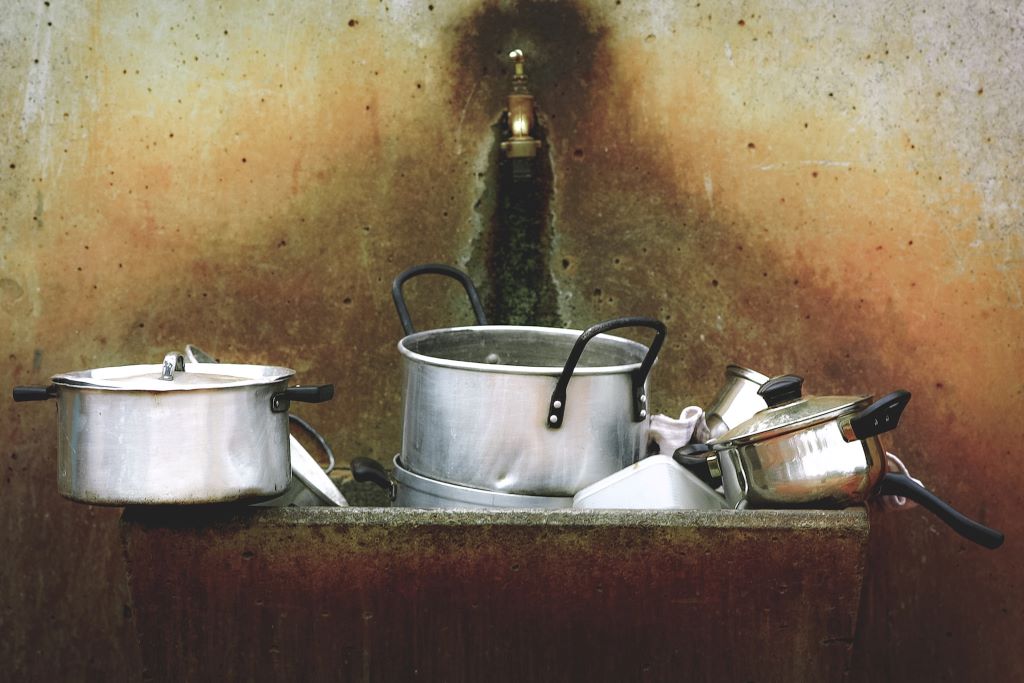

Although this is the first time lead has been found in ceramic glazes in South Africa, other kinds of kitchenware products have previously been shown to contain lead. In 2020, researchers published a study in which they purchased 20 cooking pots from informal traders and artisanal manufacturers across South Africa. Each pot was made from recycled aluminium.

They found lead in every pot, and some also contained dangerous amounts of arsenic (a known carcinogenic). The researchers cut the pots up, and boiled a piece from each one in an acidic solution. They found 11 out of the 20 pieces leached more lead than the maximum permissible limit set by the EU. (The experiment was repeated twice more on the same metal pieces, with similar results).

Thus, the authors conclude that artisanal aluminium pots are a likely source of lead exposure in the country. And the issue may extend past individual households, as the SAMRC has documented the use of artisanal aluminium pots in school feeding programmes.

Not only can lead-based artisanal pots cause lead poisoning by leaching into food, but researchers note that simply manufacturing them likely generates lead dust. As demonstrated in a small follow-up study on informal metal workshops in Kwazulu-Natal and Limpopo which found that workers had a lot more lead dust on their hands by the end of the work day than at the start.

It’s also possible that production facilities like this end up contaminating nearby residential areas. A 2018 study in the Johannesburg suburb of Bertrams found that nearly a third of all garden soil samples contained dangerous amounts of lead (i.e. lead levels that exceeded South Africa’s guidelines for safe soil). The scientists hypothesised that one reason may be that various cottage industries, including scrap metal recyclers, are interspersed among suburban homes.

Are regulations on lead being ignored?

South Africa has already taken legislative steps to deal with lead coatings. In the 2000s, a number of alarming studies found lead-based paints covering homes and playground equipment in public parks across several cities. In response, a law came into effect in 2009 that made it illegal to sell household paint or glaze that is more than 0.06% lead. Draft regulations published in 2021 will further slash this limit to 0.009% in line with recommendations by the UN. These will only become enforceable once the finalised regulations are gazetted.

Though evidence is scant, these laws may have had a positive effect. A study last year found that paints produced by large companies being sold in Botswana, but manufactured in South Africa, were all below the lead-threshold set by the 2009 law (and broadly in line with the new draft regulations as well).

However, the research on ceramics suggests the regulations have not always been adhered to, at least when it comes to glazes. The only South African-made piece of crockery which was tested in the study described earlier had a coating that contained over 100 times the amount of lead legally permissible under the 2009 law (despite the tests being conducted nine years after it was passed).

If additional research finds that the problem is widespread, then Mexico’s experience may offer one path forward. There, a ban on lead glaze has long gone unenforced. NGOs in parts of the country have responded by assisting artisanal potters to switch to lead-free glazes and to develop higher-temperature kilns (which would prevent metals from leaching). This has been coupled with public awareness campaigns about the harms of lead-based pottery and a certification program for potters using lead-free coatings.

But stakeholders say the government needs to play its part as well. The South African Paint Manufacturing Association (SAPMA) has previously urged the government to do more to enforce its regulations. In 2021 they stated that “random samples taken from hardware shelves by the government regularly showed that hazardous levels of paint were still being sold. But no report of any offender being charged by the police appeared in the press”.

The National Department of Health didn’t respond to a request for comment about this at the time of publication.

Speaking to Spotlight for this article however, the executive director of SAPMA, Tara Benn, says “I believe manufacturers are adhering to the current regulation and most if not all have already adopted the new regulation of less than 90 parts per million [i.e. 0.009%], but this regulation has not been published as yet”.

Data and investment needed

Except for a few (mostly wealthy) nations like the United States, very few countries run nationally representative blood-lead surveys. In countries like South Africa, researchers have only been able to make very rough calculations about how many people have lead poisoning by pooling together different studies that have been done in particular communities.

As a result, policy makers lack good data about the extent of the problem. National blood-lead monitoring schemes would also allow health officials to work out which communities are most affected, which in turn, could help them identify the sources of lead exposure.

Bjorn Larsen, an environmental economist who consults for the World Bank, explains: “The first thing that needs to be done is we have to get in place routine blood-lead measurements that are nationally representative…This can be done by adding a [blood-lead] module to existing routine household surveys, for example UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey…countries also have their own routine household surveys, [blood-lead tests] could be added to those”.

In the United States, all children who are enrolled in Medicaid (the government-run insurance scheme) receive blood-lead tests at ages one and two (these can be done via a simple finger-prick test) . This is in addition to nationally representative surveys which are done by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Overall, the CDC receives about four million lead test results from across the country each year.

In addition, experts are increasingly calling for greater international health financing for the prevention of lead poisoning in low- and middle-income countries. Last month, a group of experts, including researchers from Stanford and officials from UNICEF, released a joint statement on lead poisoning in developing nations. It argues that “despite the extraordinary health, learning, and economic toll attributable to lead, we find the global lead poisoning crisis remains almost entirely absent from the global health, education, and development agendas”.

The statement argues that $350 million in international aid over the next seven years would be enough to make a significant dent in the problem. They provide a breakdown of these funds, which include international assistance with enforcing anti-lead laws, purchasing lead-testing equipment and assisting companies (such as paint manufacturers) with moving away from lead-based sources.

Note: This is the second in a two-part Spotlight special series on lead poisoning. You can read part one here.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons Licence.

Source: Spotlight