Lung cancer cells that metastasise to the brain survive by convincing brain cells called astrocytes that they are baby neurons in need of protection, according to a study by researchers at Stanford Medicine published in Nature Cell Biology.

The cancer cells carry out their subterfuge by secreting a chemical signal prevalent in the developing human brain, the researchers found. This signal draws astrocytes to the tumour, encouraging them to secrete other factors that promote the cancer cells’ survival. Blocking that signal may be one way to slow or stop the growth of brain metastases of small cell lung cancer, which account for about 10% to 15% of all lung cancers, the researchers believe.

In the adult brain, astrocytes play a critical role in maintaining nerve function and connectivity. They are also important during brain development, when they facilitate connections between developing neurons.

The researchers studied laboratory mice, human tissue samples and human mini-brains, or organoids, grown in a lab dish to dissect the unique relationship between the cancer cells and their ‘big sister’ astrocytes, which hover nearby and shower them with protective factors.

“Small cell lung cancers are known for their ability to metastasise to the brain and thrive in an environment that is not normally conducive to tumour growth,” said professor of paediatrics and of genetics Julien Sage, PhD. “Our study suggests that these cancer cells reprogram the brain microenvironment by recruiting astrocytes for their protection.”

Professor Sage is the senior author of the study, while postdoctoral scholar Fangfei Qu, PhD, is the lead author.

Invasion of the brain

Small cell lung cancer excels at metastasising to the brain – about 15% to 20% of people already have clusters of cancer cells in their brains when their lung tumours are first diagnosed. As the cancer progresses, about 40% to 50% of patients will develop brain metastases. The problem is so prevalent, and the clinical outcome so dire, that clinicians recommend cranial radiation even before brain metastases have been found.

How and why small cell lung cancer has such an affinity for the brain has been something of a mystery. Brain metastases are rarely biopsied or removed because doing so has not been shown to affect a patient’s survival, and brain surgery is so invasive. Using laboratory mice is also of little help since small cell lung cancers in those animals rarely develop metastases in the brain, perhaps due to subtle biological differences between species.

Small cell lung cancers have another distinguishing feature – they are neuroendocrine cancers, meaning they arise from cells with similarities to both neurons and hormone-producing cells. Neuroendocrine cells link the nervous system with the endocrine system throughout the body, including in the lung.

Sage and his colleagues wondered whether neuronal-associated proteins on the surface of small cell lung cancer cells give them a leg up when the cells first begin to infiltrate the brain.

“We know the brain is full of neurons,” Sage said. “Maybe that’s why these cancer cells with some neuronal traits are happy in the brain and are accepted into that environment.”

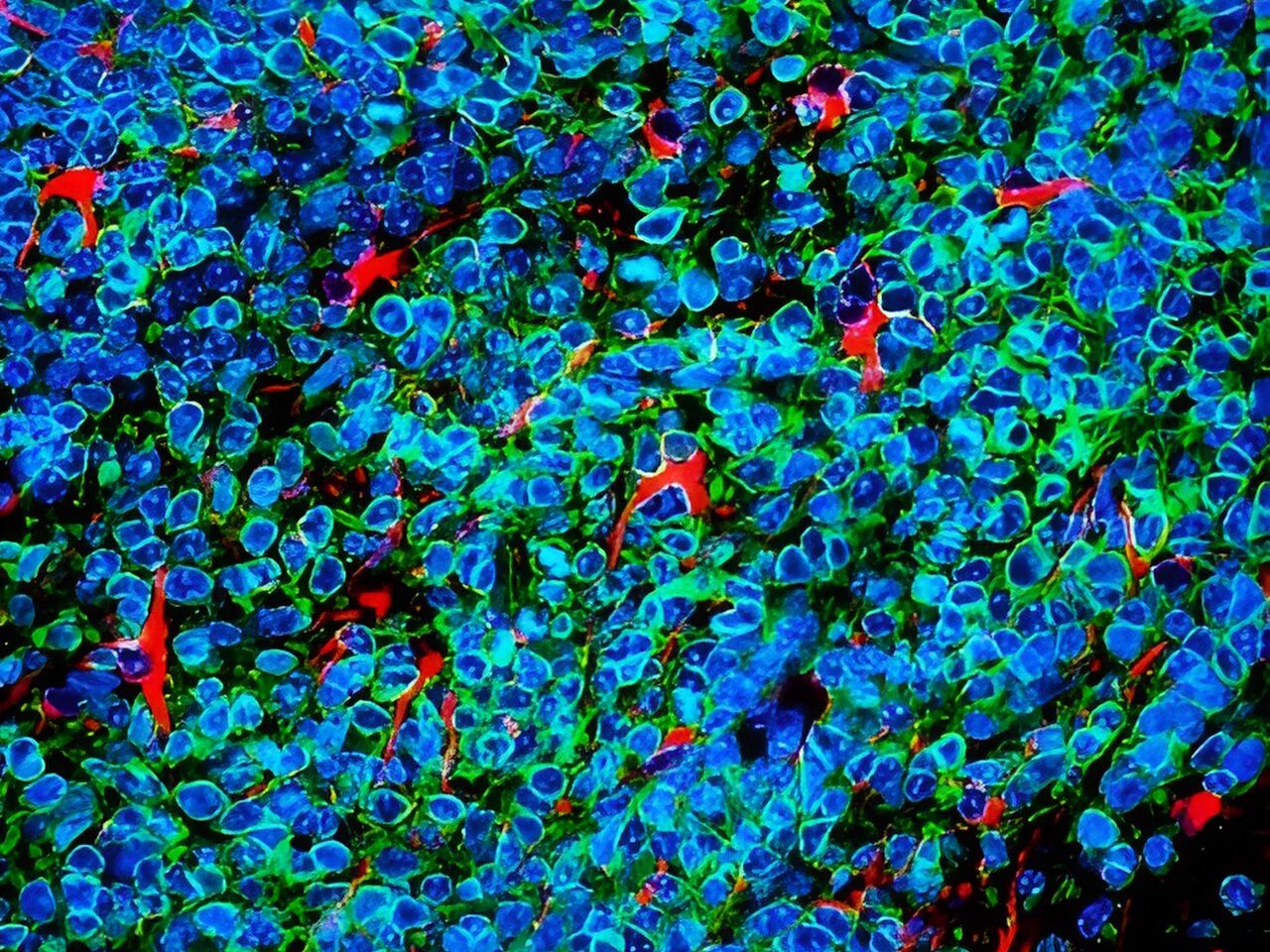

Qu and Sage developed a way to inject mouse small cell lung cancer cells grown in the laboratory into the brains of mice to spark the development of brain tumours. They saw that astrocytes, a subtype of glial cell, flocked to the infant tumours and began to churn out proteins critical during brain development, including factors that stimulate nerve growth.

A plethora of astrocytes

A similar call happens in human brains, they noted: Brain tissue samples from people who had died of metastatic small cell lung cancer, shared by professor of pathology and paper co-author Christina Kong, MD, had many more protective astrocytes in the interior of the tumours than did metastases of melanoma, breast cancer and another type of lung cancer called adenocarcinoma.

Qu worked with assistant professor of paediatrics and co-author Anca Pasca, MD, to fuse aggregates of small cell lung cancer, lung adenocarcinoma or breast cancer cells with what are called cortical organoids – in vitro-grown clumps of brain cells including neurons and astrocytes that begin to mimic the organisation and connectivity of a human cortex. Within 10 days, many more protective astrocytes had infiltrated the small cell lung cancer pseudo-tumours than the adenocarcinoma or breast cancer.

“This showed us that the astrocytes actively move toward the small cell lung cancer cells, rather than simply being engulfed by the growing tumour,” Sage said. “What’s more exciting, though, is that these organoids, or mini-brains, realistically model the developing human brain. So, we’re no longer relying on a mouse model. It’s a perfect system to study brain metastases.”

Further research showed that the small cell lung cancer cells summon protective astrocytes by secreting a protein called Reelin that mediates the migration of neuronal and glial cells during brain development. Triggering Reelin expression in mouse breast cancer cells injected into the brain significantly increased the number of astrocytes in the resulting tumours in the mice, and the tumours were larger than in control animals injected with cells with low Reelin expression.

The apparent reliance of the cancer cells on chemical signals and responses specific to the developing brain may give clues for the development of future therapies, Sage believes.

“Some of these signals may not be as relevant or as highly expressed in the adult brain,” Sage said. “As a result, perhaps they could still be targeted to slow or prevent brain metastases without harming a normal brain. This might be an important window of opportunity for therapy.”

Source: Stanford Medicine