Could a Simple Dietary Change Increase Platelet Counts?

Aside from transfusions, there currently is no way to boost people’s platelet counts, which can drop for reasons such as chemotherapy, leaving them at risk for uncontrolled bleeding. But new research published in Nature Cardiovascular Research suggests that there could be a simple alternative: a dietary change in type of fat intake could raise platelet counts in people with low levels.

A study led by Kellie Machlus, PhD, and Maria Barrachina, PhD at Boston Children’s Hospital found that they could raise platelet counts in mice by feeding them polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) like those found in the Mediterranean diet. In contrast, mice fed a diet high in saturated fatty acids had decreased platelet counts.

“We were honestly surprised at how profound the effects were,” says Machlus, whose lab focuses on studying platelets and their precursor cells, megakaryocytes, and ways to get the body to increase platelet production.

But equally interesting is the apparent reason for the dietary effect.

“What brought me to the idea of diet is that megakaryocytes make these long extensions from their membrane when they form platelets,” Machlus says. “We thought the membrane must have an unusual composition to make it so fluid.”

A fluid megakaryocyte membrane

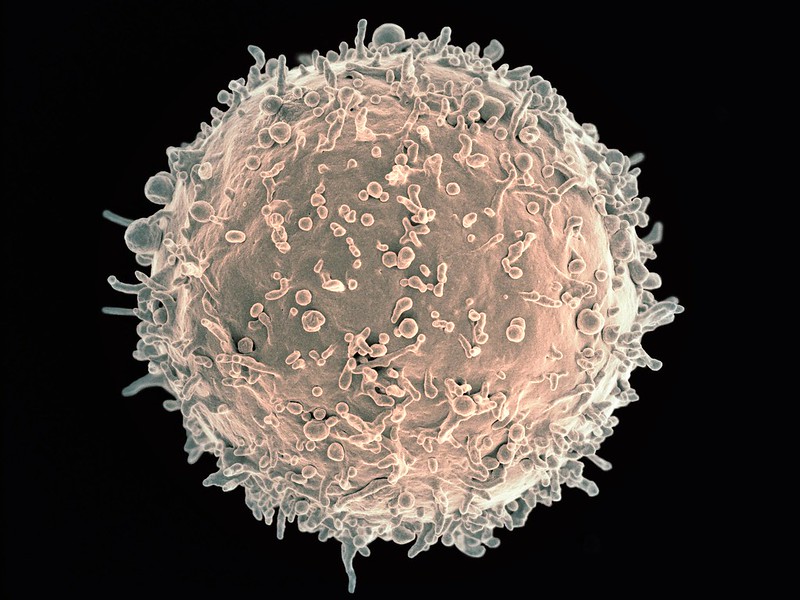

No one had studied megakaryocyte membranes before, perhaps because megakaryocytes are in the bone marrow and hard to access. Machlus, Barrachina, and their colleagues decided to comprehensively assess the membranes’ fat content with lipidomics.

“We found that PUFAs are enriched in megakaryocytes, especially right before they begin making platelets,” says Machlus. “We think they provide the fluidity necessary for the membrane to move and reshape.”

In culture, the megakaryocytes with higher amounts of PUFAs in their membrane made more platelets. When the cells were instead supplied with saturated fats as their lipid source, platelet production declined. The same thing happened when the team added compounds to inhibit uptake of PUFAs from the blood.

The researchers also identified one of the receptors on megakaryocytes that’s responsible for taking up PUFAs from blood: CD36. When they deleted the gene for CD36 in their mouse model, the animals had low platelet counts.

Serendipitously, the researchers were able to connect the dots to humans. Through a colleague in the U.K., they identified a family in which several members had a mutation in the CD36 gene. Those affected had low platelet counts and, in the mother’s case, bleeding episodes.

An olive oil intervention?

Intrigued by their findings, Barrachina hopes to extend the study by collaborating with a team in her native Spain. The team is studying dietary interventions for cardiovascular disease, including the Mediterranean diet.

“We want to look at platelets from these patients,” she says. She thinks that platelets with more saturated fatty acids in their membranes might be in a more activated state that could lead them to aggregate and form blood clots.

While Machlus thinks it may be worth encouraging patients with thrombocytopenia to consume more olive oil to increase PUFA levels, she recognises that a drug treatment may be more practical.

“Our next steps are to find out the enzymes that create PUFAs,” she says. “Maybe we can target them to make more platelets.”

Source: Boston Children’s Hospital