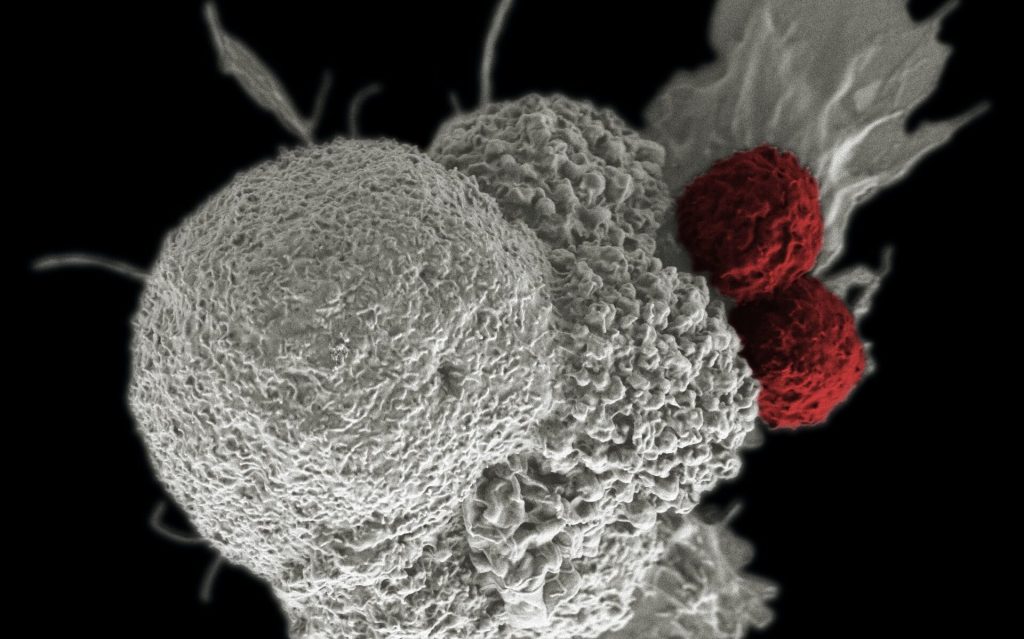

When it comes to chronic infections and cancer, cytotoxic T cells play a central role in our defences. Research published in the journal Immunity has revealed that these cells can specialise into “sprinters” to fight a strong, short-term infection or into “marathon runners” for the long battle against chronic infections and cancer.

Professor Daniel Pinschewer at the Department of Biomedicine of the University of Basel led a study into understanding how cytotoxic T cells adapt to infection and cancer.

“These T cells can become specialised in two different ways: either as a kind of sprinter or as marathon runners,” explains Pinschewer. “However, the latter can also convert into sprinters at any time, in order to stamp out an infection.”

Chronic infections are a special case: the T cells are activated and a strong inflammatory response occurs at the same time. “This tends to ‘shock’ the T cells into developing into sprinters, which can only intervene effectively in the short term to remove infected cells,” says the virologist. “If all T cells behaved like that, our immune defences would break down pretty soon.”

Biological messenger counteracts the “shock”

The researchers examined how, in spite of this, the immune system is still able to provide enough T cells for the endurance race against chronic infections. According to their results, a biological messenger called interleukin-33 (IL-33) plays a key role. It allows the T cells to remain in their “marathon runner” state. “IL-33 takes away the shock of the inflammation, so to speak,” explains Dr Anna-Friederike Marx, lead author of the study.

In addition, the biological messenger causes the marathon T cells to proliferate, so that more endurance runners are available to combat the infection. “Thanks to IL-33, there are enough cytotoxic T cells around for the long haul that can still pull off a final sprint after their marathon,” says Marx.

The findings could help improve the treatment of chronic infections such as hepatitis C. It is conceivable that IL-33 could be administered to support an effective immune response. Thinking along the same lines, IL-33 could be one key to improving cancer immunotherapy, to enable T cells to wage an efficient and long-lasting offensive against tumour cells.

Source: University of Basel