Researchers have demonstrated that the daily rhythms of the immune system – and in particular that of dendritic cells, its key sentinels – have a hitherto unsuspected impact on tumour growth. These results, published in Nature, indicate that simply changing the time of administration of a treatment could boost its effectiveness.

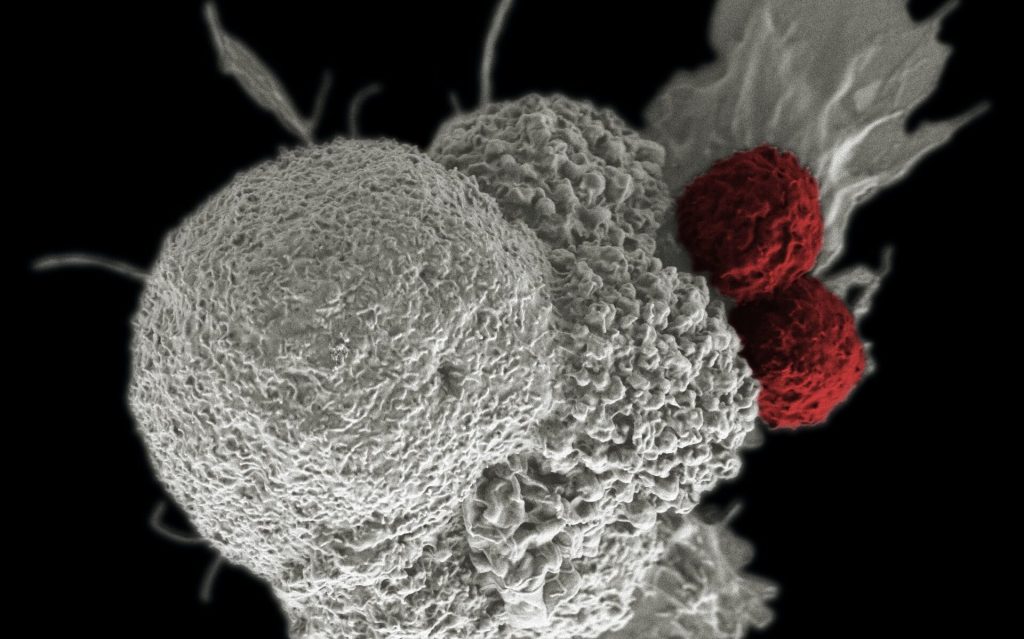

Like pathogens, cancer cells can be identified and targeted by a specific immune response, which can be enhanced by immunotherapy treatments.

In previous studies, the team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich (LMU) had shown that the activation of the immune system is modulated according to the time of day, indicating a peak of efficiency early in the morning in humans.

The immune system is no exception to the circadian rhythm. ‘‘By studying the migration of dendritic cells in the lymphatic system, one of the most essential elements of the immune response, we had highlighted the fact that immune activation oscillates throughout the day, with a peak in the late behavioural resting phase,” summarises study leader Christoph Scheiermann, professor at the University of Geneva. In the current study, the group focussed on cancer to assess how this temporal modulation affected tumours.

Temporal profiling of dendritic cells

The scientists injected groups of mice with melanoma cells at six different times of the day and then monitored tumour growth for a fortnight. ‘‘By varying only the time of injection, we observed very surprising results: tumours implanted in the afternoon grew little, while those implanted at night grew much faster, in accordance with the rhythm of activation of the mice’s immune system’’, said Chen Wang, a researcher in Christoph Scheiermann’s lab and first author of this study. The research team then reproduced the experiment with mice that had no immune system. ‘‘There was no longer any difference related to the time of day, thus confirming that the latter is indeed induced by the immune response: the first immune cells activated are the dendritic cells of the skin, which are found 24 hours later in the lymph node. The T cells are then activated and attack the tumour.” Suppressing the internal clocks of the dendritic cells causes the rhythm of activation of the immune system to disappear, confirming their key role.

Lastly, the researchers administered an immunotherapy treatment at different times of the day to mice whose tumour implantation had taken place at the same time. ‘‘This therapeutic vaccine consisted of a tumour-specific antigen, very similar to what is used to treat patients. When administered in the afternoon, the beneficial effect was again increased.’’

Findings in humans

In order to find out whether these results were repeated in humans, the scientists re-examined the data of patients treated with cancer vaccines for melanoma. Melanoma-specific T cells in these patients responded better to treatments administered early in the morning, which corresponds to the human circadian profile, reversed in comparison with mice, which are nocturnal animals. ‘‘This is very encouraging, but it is only a retrospective study of a small cohort of ten people,’’ Christoph Scheiermann points out.

The researchers now want to confirm and refine these initial findings through clinical studies. However, the very idea that a treatment can become more potent depending on the time of day opens up some surprising possibilities.

Source: University of Geneva