Early Sensing of Malaria in the Brain Leads to Cerebral Malaria

A recent study published in PNAS revealed that endothelial cells in the brain are able to sense the infection by the malaria parasite at an early phase, triggering the inflammation underlying cerebral malaria. This discovery identified new targets for adjuvant therapies that could restrain brain damage in initial phases of the disease and avoid neurological sequelae.

Cerebral malaria is a severe complication of infection with Plasmodium falciparum, the most lethal of the parasites causing malaria. This form of the disease manifests through impaired consciousness and coma and affects mainly children under 5, being one of the main causes of death in this age group in countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. Survivors are frequently affected by debilitating neurological sequelae, such as motor deficits, paralysis, and speech, hearing, and visual impairment.

To prevent certain molecules and cells from reaching the brain, which would disturb its normal functioning, endothelial cells forming a tight barrier between the blood and this organ. Cerebral malaria results from an unrestrained inflammatory response to infection which leads to significant alterations in this barrier and, consequently, neurological complications.

Over the last years, specialists in this field have turned their attention to a molecule, named interferon-β, which seems to be associated with this pathological process. So called for interfering with viral replication, this highly inflammatory molecule has two sides: it can either be protecting or cause tissue destruction. It is known, for example, that despite its antiviral role in COVID-19, at a given concentration and phase of infection, it can cause lung damage. A similar dynamic is thought to occur in cerebral malaria. However, we still don’t know what leads to the secretion of interferon-β, nor the main cells involved.

The present study revealed that endothelial cells in the brain play a crucial role, being able to sense the infection by the malaria parasite at an early phase. These detect the infection through an internal sensor which triggers a cascade of events, starting with the production of interferon-β. Next, they release a signalling molecule that attracts cells of the immune system to the brain, initiating the inflammatory process.

To reach these conclusions, researchers used mice that mimic several symptoms described in human malaria and a genetic manipulation system that allowed them to delete this sensor in several types of cells. When they deleted this sensor in brain endothelial cells, the animals’ symptoms were not as severe with lower mortality. They then realised these brain cells contributed greatly to the pathology of cerebral malaria. “We thought brain endothelial cells acted in a later phase, but we ended up realising that they are participants from the very beginning”, explained Teresa Pais, a post-doctoral researcher at the IGC and first author of the study. “Normally we associate this initial phase of the response to infection with cells of the immune system. These are already known to respond, but cells of the brain, and maybe other organs, also have this ability to sense the infection because they have the same sensors.”

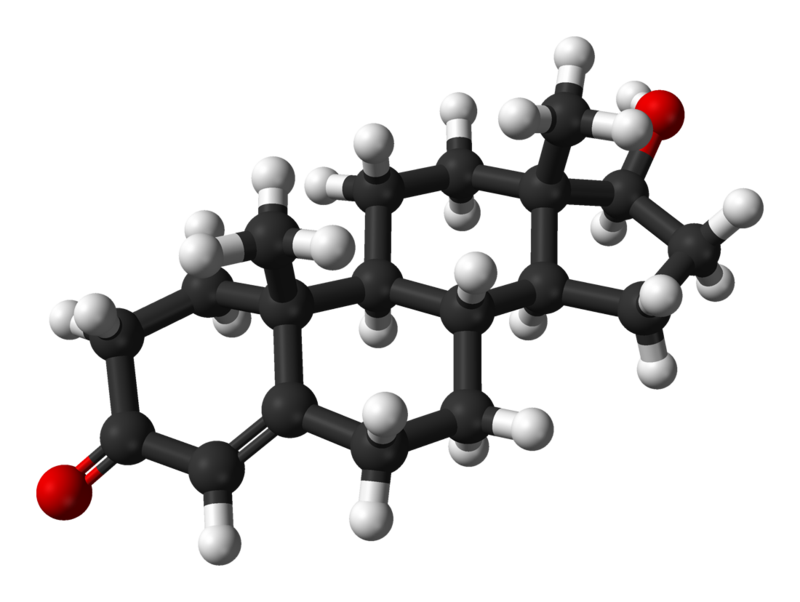

But what really surprised the researchers was the factor activating the sensor and triggering this cell response. This factor is nothing more nothing less than a by-product of the activity of the parasite. Once in the blood, the parasite invades the host’s red blood cells, where it multiplies. Here, it digests haemoglobin, a protein that transports oxygen, to get nutrients. During this process, a molecule named haeme is formed and it can be transported in tiny particles in the blood that are internalised by endothelial cells. When this happens, haeme acts as an alarm for the immune system. “We weren’t expecting that haeme could enter cells this way and activate this response involving interferon-β in endothelial cells”, the researcher confessed.

This six-year project allowed the researchers to identify a molecular mechanism that is critical for the destruction of brain tissue during infection with the malaria parasite and, with that, new therapeutic targets. “The next step will be to try to inhibit the activity of this sensor inside the endothelial cells and understand if we can act on the host’s response and stop brain pathology in an initial phase,” explained principal investigator Carlos Penha Gonçalves. “If we could use inhibitors of the sensor in parallel with antiparasitic drugs maybe we could stop the loss of neuronal function and avoid sequelae which are a major problem for children surviving cerebral malaria.”