How Macrophages Control an Uncooperative Meal

Certain pathogens such as Salmonella have developed strategies to protect themselves from the macrophages’ digesting attempts, causing severe Typhoid infections and inflammations. Scientists report in Nature Metabolism how the inter-organellar crosstalk between phago-lysosomes and mitochondria restricts the growth of such bacteria inside macrophages.

Signals from the digestion cell organelle

As scavenger cells, macrophages have a very prominent digestion organelle, the phago-lysosome, where engulfed microorganisms are commonly degraded into pieces and become inactivated. “It has long been known that the molecule TFEB (Transcription factor EB) is important for the regulation of the phago-lysosomal system. More recent evidence also suggested that TFEB supports the defense against bacteria,” said Max Planck Institute group leader Angelika Rambold.

She and her team wanted to understand how exactly TFEB mediates its anti-bacterial role in macrophages. They confirmed earlier findings showing that a broad range of microbes, bacterial and inflammatory stimuli activate TFEB and thus the phago-lysosomal system.

“It made sense that pathogen signals trigger TFEB as macrophages need a more active digestion system quickly after they devour a meal of bacteria. But, interestingly, the experiments also revealed an additional strong effect of TFEB activation on another intracellular organelle system — mitochondria. This was completely unexpected and novel to us,” said Angelika Rambold.

Instructing mitochondria to increase anti-microbial activity

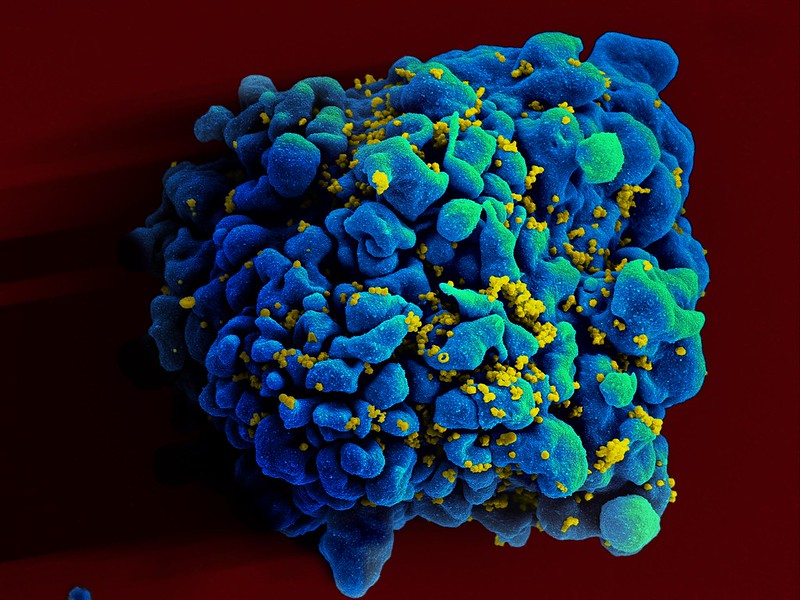

Composed of inner and outer membranes, mitochondria are the primary sites of cellular respiration and release energy from nutrients. Moreover, the mitochondria in immune cells were recently identified as sources of anti-microbial metabolites.

By using a broad experimental tool set, the investigators identified the pathway controlling an unexpected crosstalk between lysosomes and mitochondria. “Macrophages make use of extensive inter-organellar communication: the lysosome activates TFEB, which shuttles into the nucleus where it controls the transcription of a protein called IRG1. This protein is imported into mitochondria, where it acts as a major enzyme to produce the anti-microbial metabolite itaconate,” explained Angelika Rambold.

Exploiting organelle communication to control bacterial infections

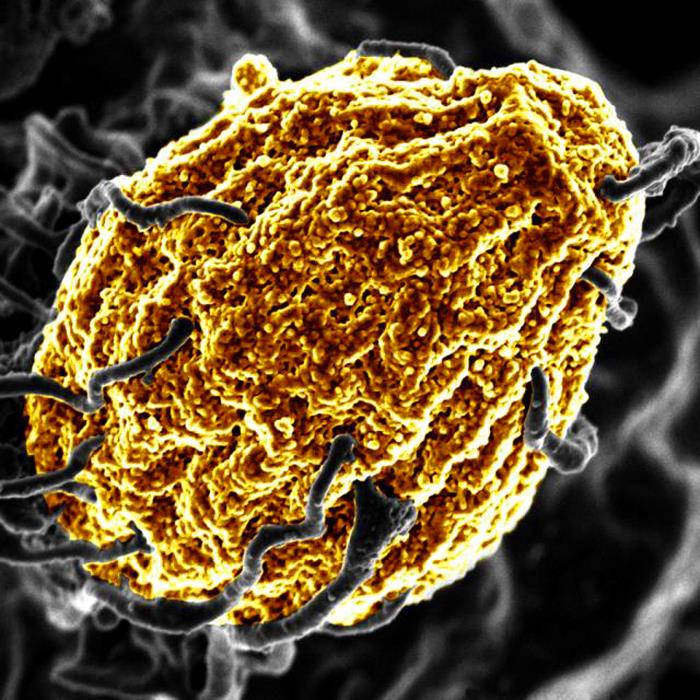

The researchers investigated whether they could make use of this newly identified pathway to control bacterial growth. “We speculated that activating this pathway could be used to target certain bacterial species, such as Salmonella,” said Angelika Rambold. “Salmonella can escape the degradation by the phago-lysosomal system. They manage to grow inside macrophages, which can lead to the spreading of these bacteria to several organs in an infected body,” explained Alexander Westermann, collaborating scientist from the University of Würzburg.

When the researchers activated TFEB in infected macrophages in mice, the TFEB-Irg1-itaconate pathway inhibited the growth of Salmonella inside the cells. These data show that the lysosome-to-mitochondria interplay represents an antibacterial defense mechanism to protect the macrophage from being exploited as a bacterial growth niche.

In light of the increasing emergence of multi-drug resistant bacteria, with more than 10 million expected deaths per year by 2050 according to the various expert groups, it becomes important to identify new strategies to control bacterial infections that escape immune mechanisms. A promising path could be to use the TFEB-Irg1-itaconate pathway or itaconate itself to treat infections caused by itaconate-sensitive bacteria. According to the researchers from more work is needed to assess whether these new intervention points can be successfully applied to humans.

Source: Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics