Why Depression Treatments May Have Different Efficacy for Women

It is not clear why women experience higher rates of depression than men, complicating treatments that are already prone to failure. Research exploring the reasons behind this found a difference in a part of the brain associated with motivation, social interactions and reward. The researchers’ findings were published in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

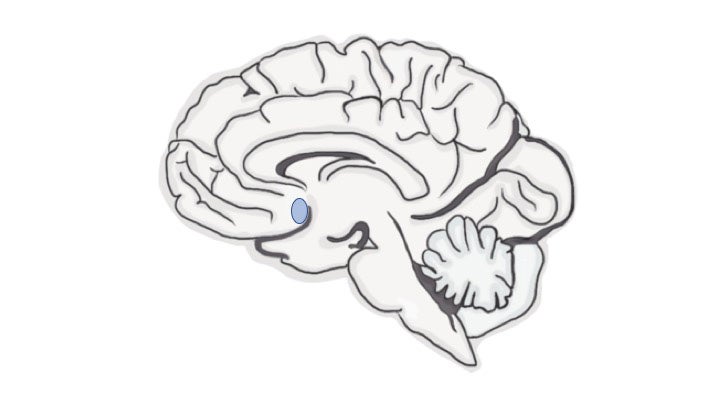

The study set out to understand how a specific part of the brain, the nucleus accumbens, is affected during depression. The nucleus accumbens is important for motivation, response to rewarding experiences and social interactions – all of which are affected by depression.

Previous analyses within the nucleus accumbens showed that different genes were turned on or off in women, but not in men diagnosed with depression. These changes could have caused symptoms of depression, or alternatively, the experience of being depressed could have changed the brain. To differentiate between these possibilities, the researchers studied mice that had experienced negative social interactions, which induce stronger depression-related behavior in females than males.

“These high-throughput analyses are very informative for understanding long-lasting effects of stress on the brain. In our rodent model, negative social interactions changed gene expression patterns in female mice that mirrored patterns observed in women with depression,” said study leader Alexia Williams, a doctoral researcher. “This is exciting because women are understudied in this field, and this finding allowed me to focus my attention on the relevance of these data for women’s health.”

After identifying similar molecular changes in the brains of mice and humans, researchers chose one gene, regulator of g protein signaling-2, or Rgs2, to manipulate. This gene controls the expression of a protein that regulates neurotransmitter receptors that are targeted by antidepressant medications such as Prozac and Zoloft. “In humans, less stable versions of the Rgs2 protein are associated with increased risk of depression, so we were curious to see whether increasing Rgs2 in the nucleus accumbens could reduce depression-related behaviorus,” said Professor Brian Trainor, senior author on the study.

When the researchers experimentally increased Rgs2 protein in the nucleus accumbens of the mice, they effectively reversed the effects of stress on these female mice, noting that social approach and preferences for preferred foods increased to levels observed in females that did not experience any stress.

“These results highlight a molecular mechanism contributing to the lack of motivation often observed in depressed patients. Reduced function of proteins like Rgs2 may contribute to symptoms that are difficult to treat in those struggling with mental illnesses,” Williams said.

Findings from basic science studies such as this one may guide the development of pharmacotherapies to effectively treat individuals suffering from depression, the researchers said.

“Our hope is that by doing studies such as these, which focus on elucidating mechanisms of specific symptoms of complex mental illnesses, we will bring science one step closer to developing new treatments for those in need,” said Williams.

Source: UC Davis