Innate Immune System Detects HIV-1 with a Two-step Strategy

Scientists have now uncovered how the innate immune system detects even very small amounts of HIV-1. The findings, published in Molecular Cell, reveal a two-step molecular strategy that jolts the innate immune response into action when exposed to HIV-1. This has important implications for developing new HIV treatments and vaccines, as well as helping understand the innate immune response in other contexts such as Alzheimer’s.

“This research delineates how the immune system can recognise a very cryptic virus, and then activate the downstream cascade that leads to immunological activation,” says Sumit Chanda, PhD, professor in the Department of Immunology and Microbiology. “From a therapeutic potential perspective, these findings open up new avenues for vaccines and adjuvants that mimic the immune response and offer additional solutions for preventing HIV infection.”

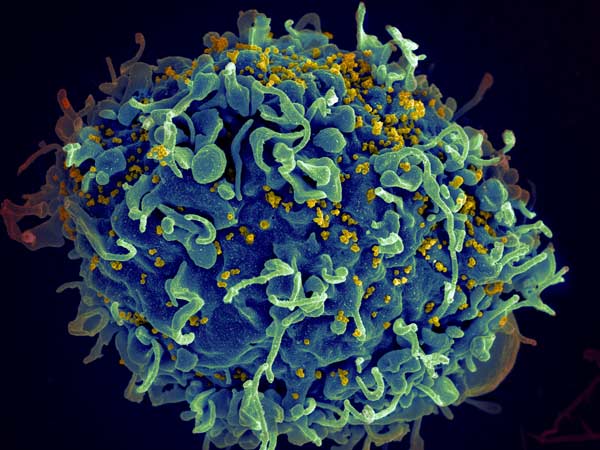

The innate immune system is activated before the adaptive immune system, which is the body’s secondary line of defense that involves more specialised functions, such as generating antibodies. One of the innate immune system’s primary responsibilities is recognizing between “self” (our own proteins and genetic material) and foreign elements (such as viruses or other pathogens). Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) is a key signaling protein in the innate immune system that senses DNA floating in a cell. If cGAS does detect a foreign presence, it activates a molecular pathway to fight off the invader.

However, because HIV-1 is an RNA virus, it produces very little DNA – so little, in fact, that scientists have not understood how cGAS and the innate immune system are able to detect it and distinguish it from our own DNA.

Scripps Research scientists discovered that the innate immune system requires a two-step security check for it to activate against HIV-1. The first step involves a protein called polyglutamine binding protein 1 (PQBP1), which recognises the HIV-1 outer shell as soon as it enters the cell and before it can replicate. PQBP1 then coats and decorates the virus, acting as an alert signal to summon cGAS. Once the viral shell begins to disassemble, cGAS activates additional immune-related pathways against the virus.

The researchers were initially surprised to find that two steps are required for innate immune activation against HIV-1, as most other DNA-encoding viruses only activate cGAS in one step. This is a similar concept to technologies that use two-factor authentication, such as requiring users to enter a password and then respond to a confirmation email.

This two-part mechanism also opens the door to vaccination approaches that can exploit the immune cascade that is initiated before the virus can start to replicate in the host cell, after PQBP1 has decorated the molecule.

“While the adaptive immune system has been a main focus for HIV research and vaccine development, our discoveries clearly show the critical role the innate immune response plays in detecting the virus,” said Sunnie Yoh, PhD, first author of the study and senior staff scientist in Chanda’s lab. “In modulating the narrow window in this two-step process – after PQBP1 has decorated the viral capsid, and before the virus is able to insert itself into the host genome and replicate – there is the potential to develop novel adjuvanted vaccine strategies against HIV-1.”

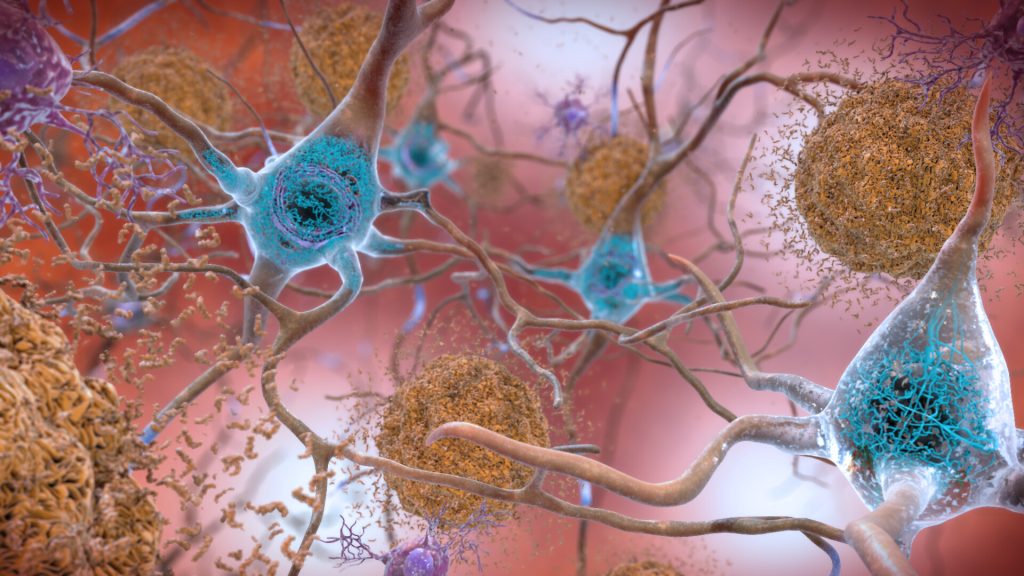

By shedding light on the workings of the innate immune system, these findings also illuminate how our bodies respond to other autoimmune or neurodegenerative inflammatory diseases. For example, PQBP1 has been shown to interact with tau – the protein that becomes dysregulated in Alzheimer’s disease – and activate the same inflammatory cGAS pathway. The researchers will continue to investigate how the innate immune system is involved in disease onset and progression, as well as how it distinguishes between self and foreign cells.

Source: Scripps Research Institute