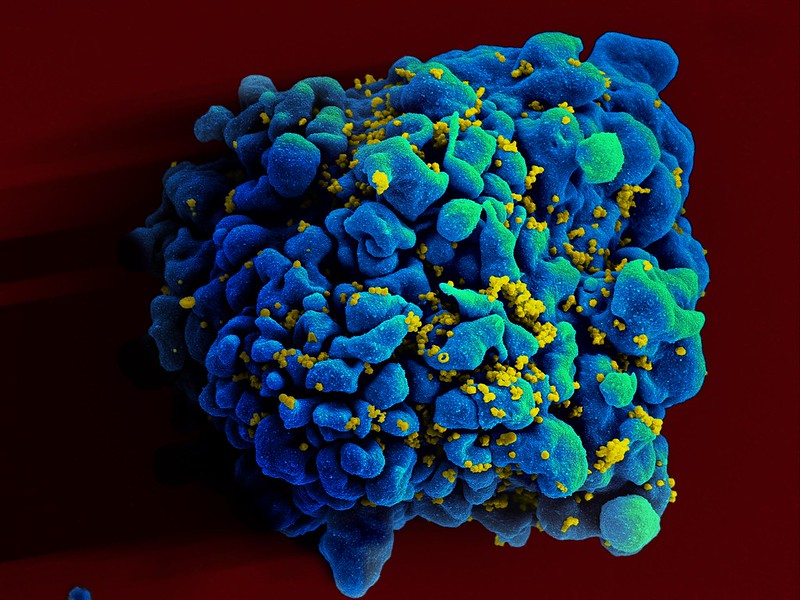

Within just two to three years of infection, HIV causes an “early and substantial” impact on ageing in infected people, accelerating epigenetic changes and telomere shortening associated with normal ageing, according to a study in iScience.

The findings suggest that new HIV infection may act to reduce an individual’s life span by five years compared to an uninfected person.

“Our work demonstrates that even in the early months and years of living with HIV, the virus has already set into motion an accelerated ageing process at the DNA level,” said lead author Elizabeth Crabb Breen, a professor emerita at UCLA. “This emphasises the critical importance of early HIV diagnosis and an awareness of ageing-related problems, as well as the value of preventing HIV infection in the first place.”

In previous studies, HIV and antiretroviral treatment has been observed to accelerate age-related conditions such as cardiovascular and renal disease, grail and cognitive impairment.

Researchers analysed stored blood samples from 102 men collected six months or less before they became infected with HIV and again two to three years after infection. They compared these with matching samples from 102 non-infected age-matched men taken over the same time period. All the men were participants in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, an ongoing US study initiated in 1984.

The study examined how HIV affects epigenetic DNA methylation. Epigenetic changes are those made in response to the influence of outside factors such as disease that affect how genes behave without changing the genes themselves.

Five epigenetic measures of ageing were analysed – four of them are epigenetic ‘ clocks’, each of which uses a slightly different approach to estimate biological age acceleration in years, relative to chronologic age. The fifth measure assessed telomere length, which shorten with age and cell divisions.

Compared to non-infected controls, HIV-infected individuals showed significant age acceleration in each of the four epigenetic clock measurements – ranging from 1.9 to 4.8 years – as well as telomere shortening over the period beginning just before infection and ending two to three years after, in the absence of highly active antiretroviral treatment.

“Our access to rare, well-characterised samples allowed us to design this study in a way that leaves little doubt about the role of HIV in eliciting biological signatures of early ageing,” said senior author Professor Beth Jamieson. “Our long-term goal is to determine whether we can use any of these signatures to predict whether an individual is at increased risk for specific ageing-related disease outcomes, thus exposing new targets for intervention therapeutics.”

Study limitations included having only men as participants, with few non-white participants. The sample size was also too small to take into consideration later effects of highly active antiretroviral treatment or to predict clinical outcomes. Additionally, there presently is no consensus on what is normal ageing or how to define it, the researchers wrote.

Source: UCLA