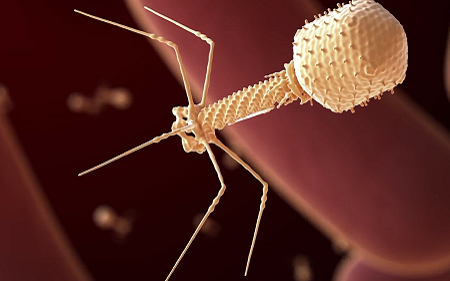

Using bacteriophages, viruses which prey on bacteria, is an emerging alternative to antibiotic use but with limited evidence. Now, with a new paper published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, collaborators report 20 new case studies on the use of the experimental treatment in Mycobacterium infections, with successes in more than half of the patients.

This is the largest ever set of published case studies for bacteriophage (or ‘phage’) therapy, giving unprecedented detail on their use to treat dire infections while laying the groundwork for a future clinical trial.

“Some of those are spectacular outcomes, and others are complicated,” said Professor Graham Hatfull at the University of Pittsburgh. “But when we do 20 cases, it becomes much more compelling that the phages are contributing to favourable outcomes – and in patients who have no other alternatives.”

The patients in the study had an infection from one or more strains of Mycobacterium, a group of bacteria that can cause deadly, treatment-resistant infections in those with compromised immune systems or cystic fibrosis. In 2019, Prof Hatfull led a team showing the first successful use of phages to treat one of these infections.

“For clinicians, these are really a nightmare: They’re not as common as some other types of infections, but they’re amongst some of the most difficult to treat with antibiotics,” said Prof Hatfull. “And especially when you take these antibiotics over extended periods of time, they’re toxic or not very well-tolerated.”

Since 2019, Prof Hatfull and his lab have fielded requests from more than 200 clinicians looking for treatments for their patients, working with them to find phages that could be effective against the particular strain of bacteria infecting each patient.

This newest paper, with collaborators from 20 institutions, dramatically expands the body of published evidence on the effectiveness of the therapy.

“These are incredibly brave physicians, jumping off the ledge to do an experimental therapy to try to help patients who have no other options,” said Prof Hatfull. “And each of these collaborations represents a marker that can move the field forward.”

Going on patient health and presence of Mycobacterium in samples, the team found that the therapy was successful in 11 out of 20 cases. No patients showed any adverse reactions to the treatment.

In another five patients the results of the therapy were inconclusive, and four patients showed no improvement. According to Prof Hatfull, even these apparent failures are key to making the therapy available to more patients. “In some ways, those are the most interesting cases,” he said. “Understanding why they didn’t work is going to be important.”

Several unexpected patterns emerged from the case studies. In 11 cases, researchers were unable to find more than one kind of phage that could kill the patient’s infection, even though standard practice would be to inject a cocktail of different viruses so the bacteria would be less likely to evolve resistance.

“If you’d asked me whether that was a good idea three years ago, I would have had a fit,” Prof Hatfull said. “But we just didn’t observe resistance, and we didn’t see a failure of treatment from resistance even when using only a single phage.”

Additionally, the team saw that some patients’ immune systems attacked the viruses, but only in a few cases did that render the virus ineffective. And in some instances, the treatment was still successful despite such an immune reaction. The study paints an encouraging picture for the therapy, said Prof Hatfull, opening up the possibility for new phage regimens that clinicians could use to maximise the treatment’s chance of success.

Along with the study’s significance to patients facing Mycobacterium infections, it also represents a substantial advance for the wider field of phage therapy. One concern is that researchers may be only publishing case studies of successful phage therapy.

“A series of consecutive case studies, where we’re not cherry-picking, is a much more transparent way of looking to see what works and what doesn’t,” said Prof Hatfull. “This adds considerable weight to the sense that the therapy is safe.”

This is still a very early stage in the development of phage therapy, and phages have not even begun to be tailored for treatment, Prof Hatfull said.

Source: University of Pittsburgh