In a groundbreaking new study, scientists report training T cells to protect against SARS-CoV-2 even without an antibody response. This could open the way to more broadly effective vaccines.

The study’s findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

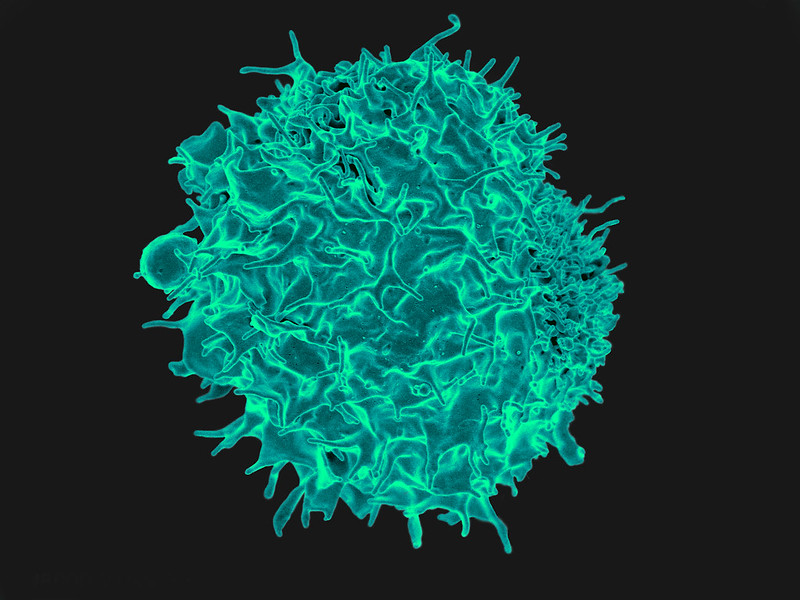

Current vaccines prompt the creation of antibodies and immune cells that recognise the spike protein. However, these vaccines were developed using the spike protein from an older variant of SARS-CoV-2, reducing their effectiveness against newer variants. Researchers have found that immune cells called T cells tend to recognise parts of SARS-CoV-2 that don’t mutate rapidly. T cells coordinate the immune system’s response and kill cells that have been infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

A vaccine that prompted the body to create more T cells against SARS-CoV-2 could help prevent disease caused by a wide range of variants. To explore this approach, a research team led by Dr Marulasiddappa Suresh from the University of Wisconsin studied two experimental vaccines that included compounds to specifically provoke a strong T-cell response in mice.

The team tested the vaccines’ ability to control infection and prevent severe disease caused by an earlier strain of SARS-CoV-2 as well as by the Beta variant, which is relatively resistant to antibodies raised against earlier strains.

When the researchers vaccinated the mice either either nasally or by injection, the animals developed T cells that could recognise the early SARS-CoV-2 strain and the Beta variant. The vaccines also caused the mice to develop antibodies that could neutralise the early strain. However, they failed to create antibodies that neutralised the Beta variant.

The mice were exposed to SARS-CoV-2 around 3 to 5 months after vaccination. Compared to the controls, vaccinated mice had very low levels of virus in their lungs and were protected against severe illness, which was true of infection with the Beta variant too. This showed that the vaccine provided protection against the Beta variant despite failing to produce effective antibodies against it.

To understand which T cells were providing this protection, the researchers selectively removed different types of T cells in vaccinated mice prior to infection. When they removed CD8 (killer) T cells, vaccinated mice remained well protected against the early strain, although not against the Beta variant. When they blocked CD4 T (helper) cells, levels of both the early strain and Beta variant in the lungs and severity of disease were substantially higher than in vaccinated mice that didn’t have their T cells removed.

These results suggest important roles for CD8 and CD4 T cells in controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection. Current mRNA vaccines do produce some T cells that recognize multiple variants. This may help account for part of the observed protection against severe disease from the Omicron variant. Future vaccines might be designed to specifically enhance this T cell response.

“I see the next generation of vaccines being able to provide immunity to current and future COVID variants by stimulating both broadly-neutralising antibodies and T cell immunity,” Dr Suresh predicted.

Source: National Institutes of Health