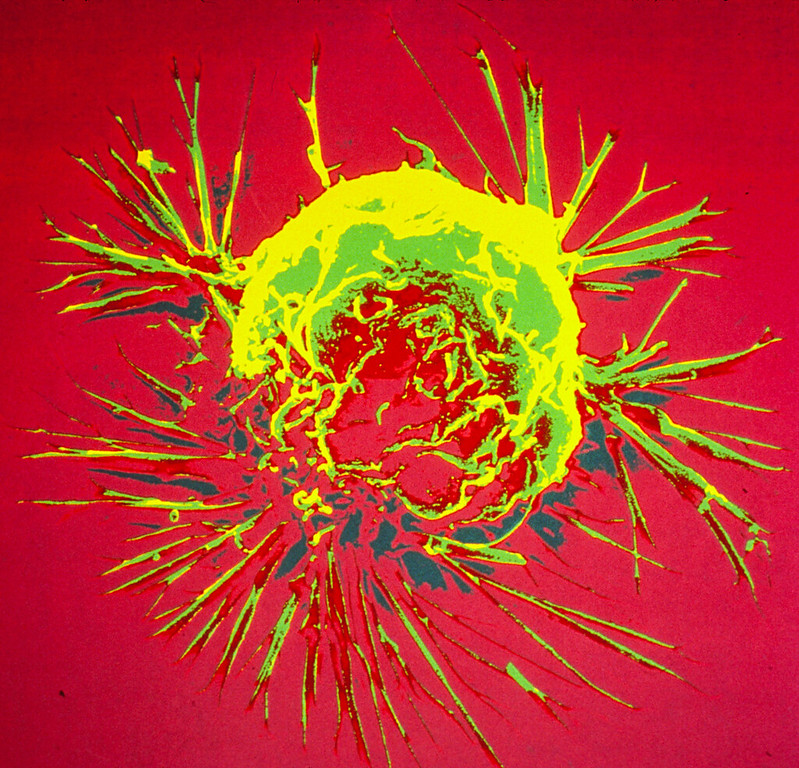

Breast cancer and diabetes have long been suspected to have some kind of relationship, but now new research in Nature Cell Biology reveals how breast cancer cells sabotage insulin production to fuel their own cravings for glucose.

Diabetes risk begins to increase two years after a breast cancer diagnosis, and by 10 years post-diagnosis, the risk is 20% higher in breast cancer survivors than in age-matched women without breast cancer.

But these epidemiological linkages are not clear-cut or definitive, and some studies have found no associations at all. In the paper, a research team describe a possible biological mechanism connecting the two diseases, in which breast cancer suppresses the production of insulin, resulting in diabetes, and the impairment of blood sugar control promotes tumour growth.

“No disease is an island because no cell lives alone,” said corresponding study author Shizhen Emily Wang, PhD, professor of pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “In this study, we describe how breast cancer cells impair the function of pancreatic islets to make them produce less insulin than needed, leading to higher blood glucose levels in breast cancer patients compared to females without cancer.”

The researchers name the culprit as extracellular vesicles (EV), which carry DNA, RNA, proteins, fats and other materials between cells, a sort of cargo communication system.

The cancer cells were found to be secreting microRNA-122 into the vesicles. When vesicles reach the pancreas, Prof Wang said, they can enter the islet cells, offload their miR-122 cargo and damage the islets’ critical function in maintaining a normal blood glucose level.

“Cancer cells have a sweet tooth,” Prof Wang said. “They use more glucose than healthy cells in order to fuel tumor growth, and this has been the basis for PET scans in cancer detection. By increasing blood glucose that can be easily used by cancer cells, breast tumors make their own favorite food and, meanwhile, deprive this essential nutrient from normal cells.”

Feeding mice slow-releasing insulin pellets or an SGLT2 inhibitor restored normal control of glucose in the presence of a breast tumour, in turn suppressed the tumour’s growth.

“These findings support a greater need for diabetes screening and prevention among breast cancer patients and survivors,” remarked Prof Wang, noting that a miR-122 inhibitor is currently in clinical trial as a potential treatment for chronic hepatitis C. It has been found to be effective in restoring normal insulin production and suppressing tumour growth in mouse models of breast cancer.

“These miR-122 inhibitors, which happen to be the first miRNA-based drugs to enter clinical trials, might have a new use in breast cancer therapy,” Prof Wang posited.