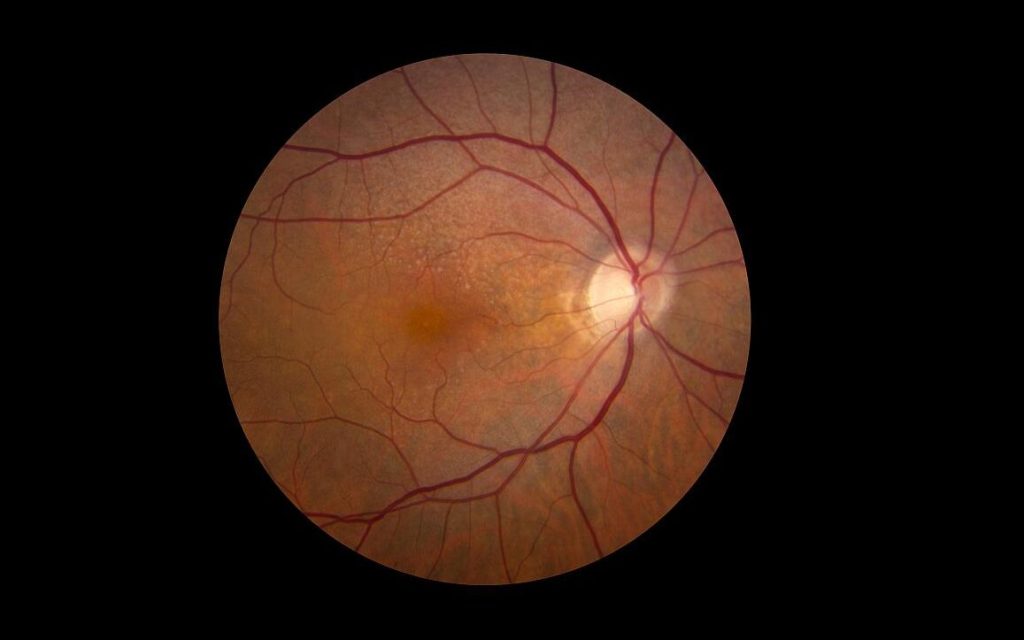

In an important step in treating a major cause of blindness, scientists have successfully identified early signs of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), in which higher number of mast cells are observed. This finding could be exploited by new treatments before symptoms develop. The study is published in PNAS.

Scientists have long known that people with certain genes on chromosomes 1 and 10 have a 2- to 3-fold higher risk of developing AMD, although lifestyle factors also play a role.

The team identified higher numbers of mast cells in the eyes of people when either of the risk genes were present, even when there were symptoms, suggesting an early mechanism in common.

They also showed the mast cells release enzymes in the back of the eye which then damage structures underneath the retina that in time is likely to damage the retina itself.

Mast cells exist in most tissues and are one of the immune system’s first defenses against infection, especially parasitic disease and damage.

Scientists already know there are more mast cells in the choroid in people with established AMD. The current study, however, identified higher levels in people before the disease develops.

The genes on chromosome 1 are linked to a part of the immune system called the complement cascade, which is associated with a risk of AMD.

Though the functional role of genes expressed by chromosome 10 are not known, but increased risk of AMD is.

Dr Richard Unwin, one of the study leaders, said: “What is really exciting about this work is that we are studying tissue from people before they have signs of the disease. This gives us a look into the very earliest stages, and gives us hope that we can intervene to stop the disease developing and ultimately prevent loss of vision”

The scientists used healthy human eye tissue donated post mortem to the Manchester Eye Tissue Repository.

They identified those who are at risk of developing age-related macular degeneration based on their risk genes, and discovered underlying changes in the tissue of the otherwise healthy at-risk individuals.

They collected retinal tissue from the back of donor eyes post mortem, following removal of the cornea for transplantation.

Then they took a small sample from the macula and removed the cells to leave a thin layer of membrane which supports the photoreceptors called rod and cone cells and is where disease begins.

They analysed the proteins present in the membrane from 30 people using mass spectrometry, which identifies protein components based on their mass, to find differences in the tissue make-up between those with and without genetic risk of AMD.

The mass spectrometry, identified a series of enzymes which are made almost exclusively by mast cells. In tissue from an additional 53 people, higher levels of mast cells were found in patients with higher disease risk.

Dr Unwin added: “We next need to look at how mast cells are activated, and whether by preventing, or clearing mast cell activation we can slow or stop disease development. There are several researchers and companies looking at complement mediated-therapies for AMD and while these are promising for Chr1-related disease there is no evidence that they will have an effect on Chr10 disease. A therapy designed to target mast cell activation as a unified mechanism could in theory treat all patients with AMD and prevent sight loss.”

Source: University of Manchester