Can Public Clinics Be Fixed with The Right Technology?

Investigating the state of affairs in public clinics, Spotlight’s Daniel Steyn and Vusi Mokoena investigate whether the right technology could help them out of their predicament.

“I never look forward to clinic day,” says Nomtsato Tsietsi, 74, on a Monday morning while standing in the queue at Kayamandi Clinic in Stellenbosch, which she visits up to three times a month to collect pills, consult with a doctor, and have her blood tests taken.

Tsietsi has several diseases including diabetes and hypertension (high blood pressure). “We sit there for too long, sometimes all day,” she says.

Her experience is typical for people visiting state clinics. But for about 80% of South Africans, this is the only option: for most people private healthcare is unaffordable and public clinic services are free.

Some patients in the Kayamandi clinic queue said they sometimes pay people up to R80 to stand in the queue for them. One man, who had been paid by someone to stand in the queue, said that he had been there since 5am.

For employed people, a day at the clinic typically means taking a day off work, often without pay.

The pubIic health system is beset with problems: long waiting times, insufficient record keeping, poorly maintained infrastructure, and poor service delivery.

A 2018 study of nurses and doctors in Cape Town found that of 16 essential skills, ten were not performed in more than half of the consultations. In more than 60% of consultations, nurses and doctors in Cape Town did not greet patients, and in 90% of consultations, they did not attempt to understand the patient’s perspective. In nother study, 76% of Cape Town-based doctors in primary care reported that they are suffering from burnout.

During our visit to Kayamandi Clinic, we asked patients whether they would embrace technological solutions to make the experience more efficient. They all said they would. Almost all of them are smartphone users and some said they could not understand why appointments cannot be made and managed digitally, or why they cannot communicate with health workers online rather than in person.

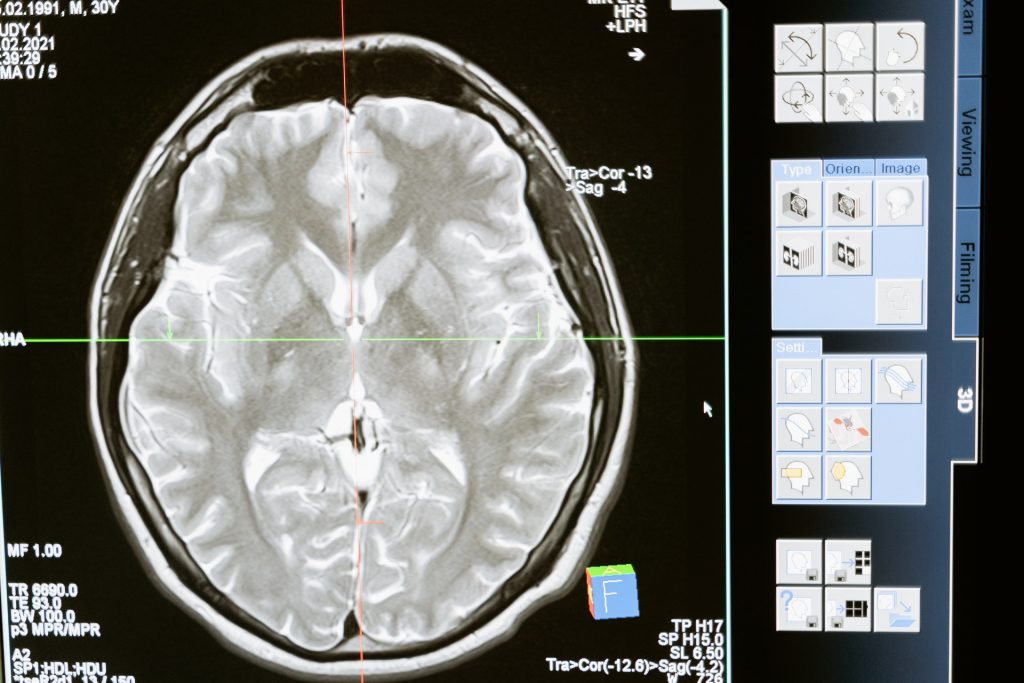

Innovative technology solutions for primary care exist in South Africa. Phukulisa Health Solutions, for example, offers a platform that mimics a consultation with a healthcare practitioner. Equipped with Bluetooth sensors, the platform can screen patients for a range of health issues, focused specifically on HIV, TB, diabetes, and heart diseases.

Phukulisa’s CEO Raymond Campbell says that this testing and screening platform offers a more efficient screening service with a faster turnaround time. For example, the platform has been tested at an antenatal unit in Mamelodi, where the platform provided test results within 14 minutes, opposed to the usual 23 hours.

But Campbell says there is little interest from the public sector in his technology. Instead, he is finding more success licensing the platform to players in the private sector.

There have been some attempts to use innovative computer technology in public sector clinics. In Limpopo, the deputy director-general of the health department, Dr Muthei Dombo, has the vision to create a “clinic in the cloud”.

In 2018, Dombo partnered with the Mint Group to conduct a trial funded by Microsoft at Rethabile clinic. Dombo provided the team at Mint Group with several problems to solve.

The team, led by Peter Reid, developed a technology to alleviate the high rate of fraud at medicine dispensing points, the difficulty of transferring medical records between different clinics, and the long waiting times.

When a patient entered the clinic, they would register at reception. Their identity document would be scanned and a picture would be taken of the patient. At every station in the clinic visited by the patient, a camera would identify the patient and the patient’s records would pop up on the screen. When the patient left the station, the profile would automatically lock.

This ensured that only patients due for specific medication would receive that medication, thereby eliminating fraud. Because the records were all kept in the cloud, the records could easily be transferred to another clinic. Without this technology, patients need to return to the same clinic every time they need to restock their medication.

The trial also assisted with queue management. Upon entering the clinic, patients would choose a “journey” based on their reason for visiting the clinic. The system would then guide the patient from one station to the next on big screens on the wall. This made the journey more seamless while also providing visual feedback to officials at the clinic helping them to manage the queues more effectively.

The trial ended shortly before the start of the Covid pandemic. The project has not yet been restarted.

One project that has been implemented widely in the public sector is Vula Mobile. Founded by Dr William Mapham in 2014, Vula aims to bridge the gap between health workers and specialists.

There is a shortage of specialist doctors in the public sector and health workers at the primary care level often lack the information to refer patients to a relevant specialist.

With the Vula app, a nurse seeing a patient can be linked with the closest specialist. Through the built-in chat function, the nurse can provide the specialist with all the necessary info and refer the patient.

The app is available in six provinces with an emphasis on the Eastern Cape. More than 24,000 health workers are registered on the system.

But other innovators in the health space, frustrated by the public sector, are focusing on providing affordable private healthcare. This follows a growing trend in South Africa, as medical aid providers increasingly offer more affordable packages targeted to lower-income earners.

At the Kayamandi clinic during GroundUp’s visit, Mcoleseli Mlenze, a 34-year-old father who often visits the clinic for hypertension medication or when his son is sick, said that while he uses the clinic to collect medication, he has started seeing a private doctor when he is sick.

He says he cannot really afford the private doctor, which costs upwards of R350 per consultation. If there was some middle-ground where he could pay R150-R200 for a consultation at a clinic that is faster and more efficient, he would happily do so.

Others in the queue said they would pay up to R50 for a better healthcare experience.

Saul Kornik, the founder of Healthforce and the Kena App, aims to lower the cost of quality primary health care so that millions of people have access to it.

Available in almost 500 pharmacies throughout the country, Healthforce’s technology enables nurses to conduct all necessary screenings and diagnostic procedures. If and when a doctor becomes necessary, the nurse presses a button to start a video call with one of the doctors in the Healthforce network.

The nurse and patient can both see the doctor and the doctor, with the help of the nurse, can consult the patient. This reduces the amount of time that the doctor is needed, thereby reducing the cost.

The patient ends up paying on average R70 to R90 for the nurse and R115 to R250 for the doctor. If needed, the doctor can prescribe medication that the patient can purchase at the pharmacy or pick up from a government dispensary.

There are Healthforce doctors available to speak any of the 11 official languages and they are available seven days a week.

In March, Healthforce launched the Kena Health app, through which patients can have consultations with nurses, doctors and mental health practitioners via chat, voice or video. The first three consultations per year are free.

After the consultation, if necessary, the doctor can provide a script for medication and a sick note.

At Kayamandi clinic, Gcobisa Malithafa, a 30-year-old mother of a toddler told GroundUp that although she would pay a small amount for a better experience, it should not have to come to that.

Malithafa suggests that instead, the clinic’s management should consult the community on a regular basis and make immediate improvements to the running of the clinic. “This thing of having one doctor at the clinic is not right,” she says.

She is struggling to get her child immunised, having visited the clinic many times without success.

Whether they use technology or not, she says, something has to change.

By Daniel Steyn and Vusi Mokoena

Republished from the original at GroundUp under a Creative Commons Licence