A team of biologists has discovered a factor that increases cellular plasticity can explain why, in breast cancer, metastases spread to the bones. Their findings appear in the journal Nature Communications.

The organs affected by cancer metastases depend in part on their tissue of origin – in the case of breast cancer, they usually form in the bones. No cure for metastatic breast cancer exists yet, and it is associated with a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of 26%. However, treatments can improve and extend the lives of patients.

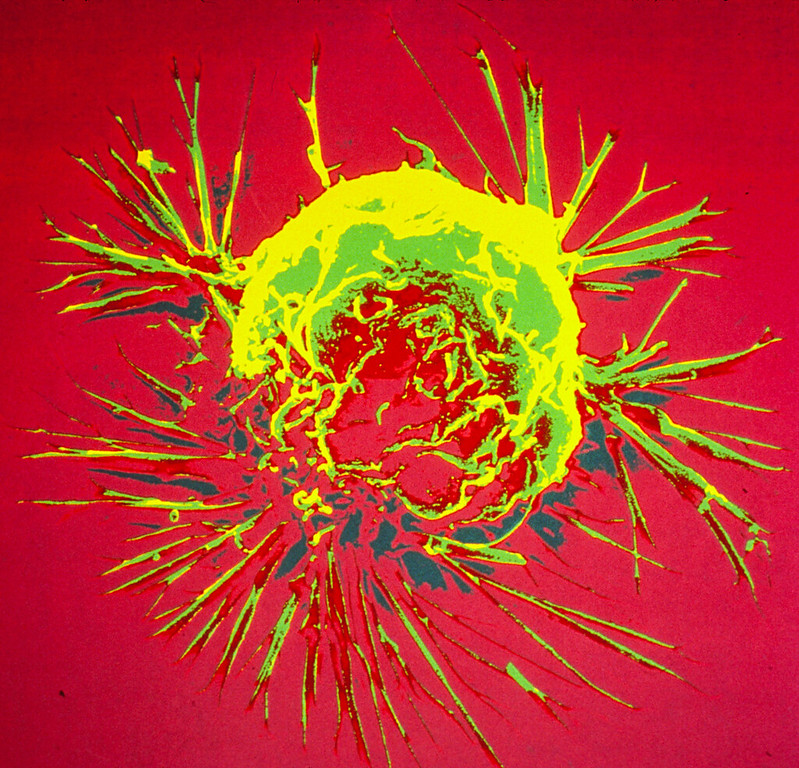

From the primary site of a tumour, cancer cells can invade their microenvironment and then circulate via blood and lymphatic vessels to distant healthy tissue to form metastases. In the case of metastatic breast cancer, the cancer cells primarily colonise the bones, but can also be found in other organs such as the liver, lungs or brain.

Plasticity of tumour cells

Although the mechanisms behind the different stages of the metastatic process are not yet fully understood, cellular plasticity plays an important role: tumour cells that become metastatic change their shape and become mobile.

Using mice, the researchers investigated the potential role of the protein ZEB1, known to increase cell plasticity, in breast cancer cell migration.

“Unlike in women, mice transplanted with human breast cancer cells develop metastasis to the lungs, not the bones. We therefore sought to identify factors capable of inducing metastasis in bone tissue and in particular tested the effect of the factor ZEB1.,” explained researcher Nastaran Mohammadi Ghahhari, first author of the study

Directing metastasis to bone

In in vitro migration and invasion experiments, the scientists found that cancer cells expressing ZEB1 moved to bone tissue, unlike cancer cells that did not express it. These results were later confirmed when human breast cancer cells were transplanted into the mammary glands of mice. If the cancer cells did not express ZEB1, metastasis occurred primarily in the lungs. In contrast, when ZEB1 was present, metastases also developed in the bones, as is the case in women.

‘‘We can therefore assume that this factor is expressed during tumour formation and that it directs cells that have acquired metastatic characteristics to the bones,’’ explained Didier Picard, the study’s last author. These findings confirm the importance of plasticity in metastases, and could help lead to new therapies.

Source: University of Geneva