Phage therapy is a long-standing technique which makes use of bacteriophage viruses to kill bacteria, but poses the challenge of some strains working in vitro but failing in vivo. Scientists have now found that gut bacteria alter their gene expression to avoid attack by bacteriophages. This research, published in Cell Host & Microbe, helps explains the difference in bacteriophage efficacy.

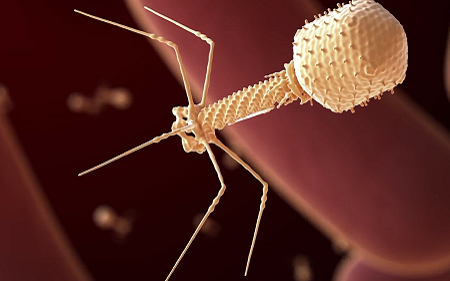

Phage therapy is a medical approach that involves treating bacterial infectious diseases using the natural ability of certain viruses, known as bacteriophages, to kill bacteria that they specifically recognise. Following the development of antibiotics, the West saw a significant decline in the use of this century-old therapeutic strategy. In the face of the growing threat of antibiotic resistance, scientists are returning to bacteriophages and to understand their mechanism of action.

Bacteria and bacteriophages are the most abundant entities in the human gut microbiota. Although bacteriophages kill bacteria, the two antagonist populations coexist in a balance in the gut.

To date, there has been little data on how phage therapy works in vivo. Interactions between bacteria and bacteriophages have, in contrast, been extensively studied in vitro. In these conditions, bacteriophages quickly infect bacteria, replicate, and destroy bacteria, while releasing new viruses capable of infecting other bacteria. However, the dynamics observed between these two microorganisms are very different in mammalian guts. Some bacteriophages that are effective in culture medium are totally ineffective in the gut environment.

In order to understand this difference, scientists decided to compare the gene expression profile, or transcriptome, of the bacterium Escherichia coli in both contexts: culture media and the gut. Using this method, they revealed genetic regulations that characterise the bacterium’s adaptation to the gut environment.

By closely examining the genes involved in this adaptation, they revealed four genes that modulate the bacterium’s susceptibility to bacteriophages. “We observed that certain genes required for infection by bacteriophages are expressed less in the gut than in vitro, thus protecting bacteria from bacteriophages,” commented Laurent Debarbieux, last author of the study.

The scientists verified their theory by eliminating the expression of one particular gene. They observed that bacterial susceptibility to a bacteriophage was significantly reduced. As a result, bacteria in the gut are able to resist predation by bacteriophages by modulating the expression of certain genes rather than mutating their genome.

This study therefore demonstrates that environment plays a predominant role in interactions between bacteria and bacteriophages. These findings pave the way for improved use of bacteriophages for therapeutic purposes.

Source: Pasteur Institute