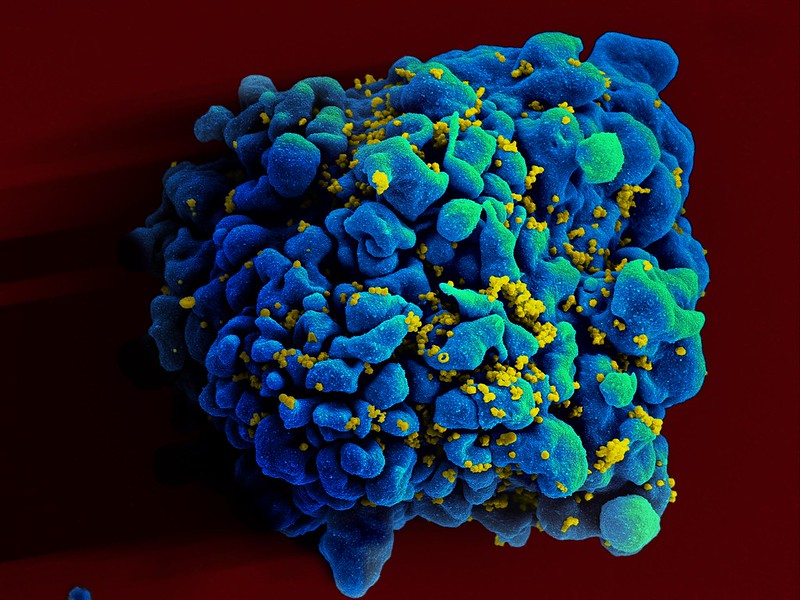

A trial has successfully used a novel treatment of anti-HIV antibodies to achieve viral suppression in several HIV patients. The results published in Nature, would enable a treatment not reliant on vigilant daily dosing and which could potentially reduce the body’s reservoir of HIV, something antiretroviral drugs cannot do. The antibody treatment could be used in combination with long-acting antiretrovirals, or alone after such medications have sufficiently brought down viral levels.

“The idea is that you would still be on HIV treatment, but instead of having to take a pill every day, with the long-acting versions of the antibodies, patients would be able to take infusions every six months,” said Professor Marina Caskey, who co-led the study.

In this trial, 18 participants received seven infusions of a pair of broadly neutralising antibodies over five months, while discontinuing their antiretroviral medications. Thirteen of these participants maintained viral suppression for at least five months, and in a few cases over a year, suggesting the antibodies are able to control viruses that are sensitive to the antibodies and prevent viral levels from rising to dangerous levels.

Besides suppressing the virus, antibody therapy may also have an effect on cells infected with HIV that cannot be eliminated by antiretroviral drugs. “Ultimately, with any treatment, we’d like to see a decline in the reservoir of infected T-cells, which fuel rebound when therapy is discontinued,” says Christian Gaebler, an assistant professor of clinical investigation in Nussenzweig’s lab and the study’s first author. After therapy, the team detected a decrease in the infected T-cells, specifically those that harbor intact viruses capable of replication. “It’s a promising finding that we hope to follow up on in future, larger studies,” Gaebler says.

The new study built on a previous, shorter trial in which participants had received three antibody infusions over six weeks. The researchers found that administering additional infusions was generally safe and well-tolerated, and the longer treatment period did not result in the emergence of new resistant variants.

Source: Rockefeller University