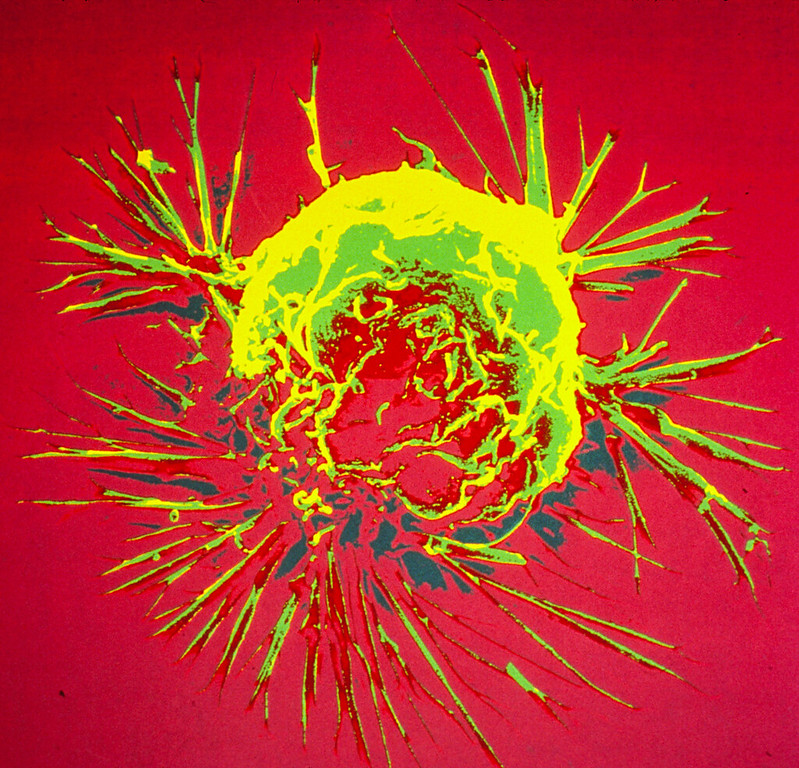

Researchers have found that bacteria lurking inside tumours promote cancer metastasis. They do so by enhancing the strength of host cells against mechanical stress in the bloodstream, promoting cell survival during tumour progression, researchers report in the journal Cell.

“Our study reveals that the cancer cell’s behaviour is also controlled by the microbes hiding inside tumours, the majority of which were originally thought to be sterile,” said senior author Shang Cai of the Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine. “This microbial involvement is distinct from the genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic components that most cancer drugs target.”

“However, our study does not mean that using antibiotics during cancer treatment will benefit patients,” he cautioned. “Therefore, it is still an important scientific question of how to manage the intratumor bacteria to improve cancer treatment in the future.”

It is known that microbes play a critical role in affecting cancer susceptibility and tumour progression, particularly in colorectal cancers. New evidence suggests however that, in a broad range of cancer types, they also form integral components of the tumour tissue itself, such as pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, and breast cancer. Microbial features are linked to cancer risk, prognosis, and treatment responses, yet the biological functions of tumour-resident microbes in tumour progression remain unclear.

Whether these microbes are actually drivers of tumour progression has been an intriguing question. “Tumour cells hijacked by microbes could be more common than previously thought, which underscores the broad clinical value of understanding the exact role of the tumour-resident microbial community in cancer progression,” Cai explained.

To find answers, Cai’s team utilised a mouse model of breast cancer with significant amounts of bacteria inside cells, similar to human breast cancer. The bacteria were found to be capable of travelling through the circulatory system with the cancer cells, playing critical roles in tumour metastasis. These passenger bacteria have the capacity to modulate the cellular actin network, promoting cell survival against mechanical stress in circulation.

“We were surprised initially at the fact that such a low abundance of bacteria could exert such a crucial role in cancer metastasis. What is even more astonishing is that only one shot of bacteria injection into the breast tumour can cause a tumour that originally rarely metastasises to start to metastasise,” Cai said. “Intracellular microbiota could be a potential target for preventing metastasis in broad cancer types at an early stage, which is much better than to have to treat it later on.”

While intratumour bacteria was found to have a clear role in promoting cancer cell metastatic colonisation, the authors did not exclude the possibility that the gut microbiome and immune system may act together with intratumour bacteria to determine cancer progression. Future in-depth analyses of how bacteria invade tumour cells, how intracellular bacteria are integrated into the host cell system, and how bacteria-containing tumor cells interact with the immune system will help inform how to properly deploy antibiotics in cancer treatment.

Source: ScienceDaily