In the human gut, individual strains of Candida albicans are incredibly varied, and some C. albicans strains may damage the gut of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to a new study published in Nature. The findings suggest a possible way to tailor treatments to individual patients in the future.

The researchers used an array of techniques to study Candida strains from the colons of people with or without ulcerative colitis, a chronic, relapsing and remitting inflammatory disorder of the colon and rectum and one of the main forms of IBD. They found that certain strains, which they call “high-damaging,” produce candidalysin, a potent toxin that damages immune cells.

“Such strains retained their “high-damaging” properties when they were removed from the patient’s gut and triggered pro-inflammatory immunity when colonised in mice, replicating certain disease hallmarks,” said senior author Dr Iliyan Iliev, an associate professor of immunology in medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

IBD is estimated to affect between one in 11 and one in 26 people worldwide. The condition can significantly impact patients’ quality of life. There are a handful of available therapies, but treatments may not always be effective. The study showed that steroids, one of the common treatments, may not work. Treating mice with steroids to suppress intestinal inflammation failed in the presence of “high-damaging” C. albicans strains.

“Our findings suggest that C. albicans strains do not cause spontaneous intestinal inflammation in a host with intact immunity,” Dr Iliev said. “But they do expand in the intestines when inflammation is present and can be a factor that influences response to therapy in our models and perhaps in patients.”

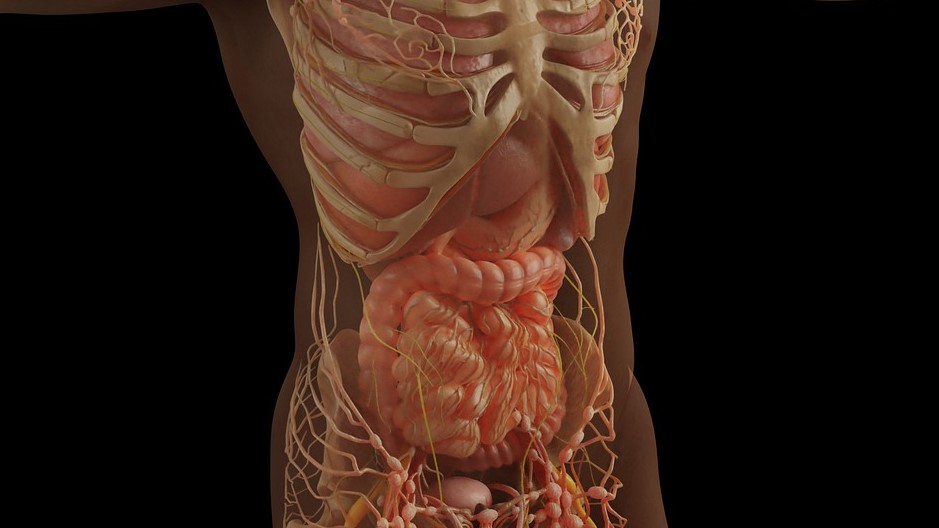

Most studies of the human microbiome in healthy individuals and those with IBD have focused on bacteria and viruses, but recent studies by Dr Iliev and others has highlighted the role of fungi. Intestinal fungi play an important role in regulating immunity at surfaces exposed to the outside, such as the intestines and lungs, due to their potent immune-stimulating characteristics. While the mycobiota – the body’s fungi community – has been linked to IBD, the pro-inflammatory of gut the mycobiota was not understood.

In the new study, the investigators initially found that Candida strains, while highly diverse in the intestines of both patients with and without colitis, were on average more abundant in the patients with IBD. But that did not explain disease outcomes in individual patients. So, the investigators set out to identify the characteristics of these strains that cause damage and how they relate to individual patients.

The researchers observed that in the patients with ulcerative colitis, severe disease was associated with the presence of “high-damaging” Candida strains, all of which produce the candidalysin toxin. The scientists showed that the toxin damages immune cells called macrophages, prompting a storm of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β.

The researchers then grew macrophages in the presence of Candida strains and found that the ability of the strains to induce IL-1β corresponded closely to the severity of colitis in the patients.

“Our finding shows that a cell-damaging toxin candidalysin released by “high damaging” C. albicans strains during the yeast-hyphae morphogenesis triggers pathogenic immunological responses in the gut,” said first author Dr Xin Li.

Experiments in mice delineated that candidalysin-producing “high-damaging” strains induced the expansion of a population of T cells called Th17 cells and other inflammation-associated immune cells, such as neutrophils.

“Neutrophils contribute to tissue damage and their accumulation is a hallmark of active IBD,” said Dr Ellen Scherl, a professor of inflammatory bowel disease. “The indication that these processes might in part be driven by a fungal toxin released by yeast strains in specific patients could potentially inform personalized treatment approaches.”

Consistent with this finding, blocking IL-1β signalling had a dramatic effect in reducing colitis signs in mice that harboured these highly pro-inflammatory strains. The researchers noted that other recent studies have linked IBD to IL-1β in a general way, prompting ongoing investigations of drugs targeting related pathways as potential IBD therapies.

“We do not know whether specific strains are acquired by specific patients during the course of disease or whether they have been always there and become a problem during episodes of active disease” Dr Iliev said. “Nevertheless, our findings highlight a mechanism by which commensal fungal strains can turn against their host and overdrive inflammation.”

The team’s next steps are to investigate the persistence candidalysin-producing strains in the inflamed colon of specific IBD patients, as well as ways to choose patients for mycobiome therapy.

Source: Weill Cornell Medicine