In an article awaiting peer review, doctors in South Africa report on the case of a 22-year-old female with uncontrolled advanced HIV infection and a SARS-CoV-2 infection that lasted 9 months, during which time the virus accumulated more than 20 additional mutations. Antiretroviral therapy suppressed HIV and cleared the coronavirus within 6–9 weeks.

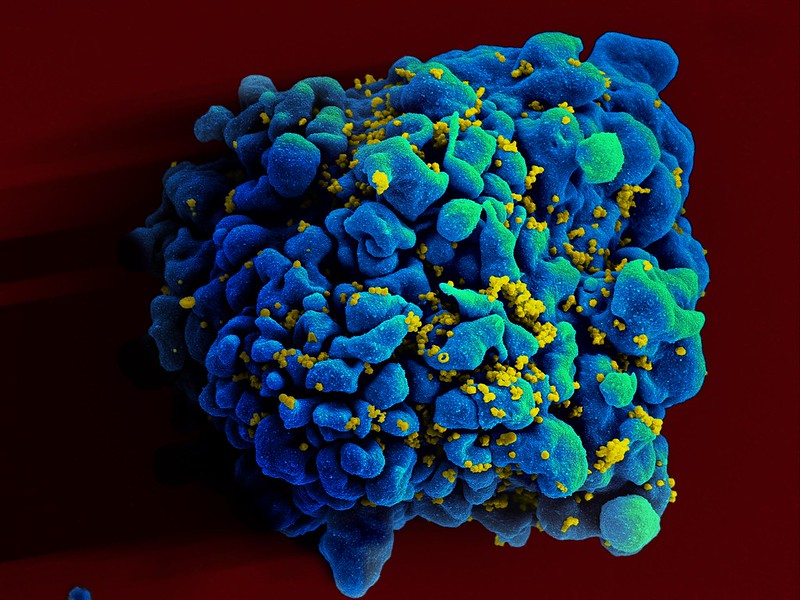

One hypothesis for novel variants is that they arise in severely immunocompromised individuals. Being unable to clear the virus because of a weakened immune response results in a persistent infection, letting mutations accumulate – some of which may allow immune evasion. In one case, SARS-CoV-2 in a female leukaemia patient developed seven mutations over three months of infection.

The authors describe a case of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection, lasting for at least 9 months, in a severely immunocompromised woman with HIV that had challenges with adherence to antiretroviral therapy.

In mid-September 2021, a female in her 20s was admitted to a tertiary hospital in Cape Town with a one-week history of sore throat, malaise, poor appetite and dysphagia. The patient was infected with HIV at birth. In January 2021, her antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen had been changed to tenofovir, emtricitabine and efavirenz, but she had difficulty adhering. In August 2021 she moved from rural KwaZulu-Natal to Cape Town. She stated that she had not received a COVID vaccination.

“On physical examination, the patient was wasted but had no palpable lymph nodes,” the authors report. “She was awake and lucid, with no focal neurological deficits. She was not in respiratory distress with an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The cardiovascular and abdominal examinations, renal function, white cell count and liver enzymes were without abnormalities. Her CD4 count was 9 cells/μL and her plasma HIV viral load 4.60 log10 viral RNA copies/mL, indicating advanced HIV infection, poorly controlled by ART.

“During a prolonged hospital stay the patient experienced multiple complications requiring treatment. Following adherence counselling, antiretroviral therapy was reinitiated with a new regimen of tenofovir/efavirenz/dolutegravir a week after admission.”

The patient tested positive for COVID on 25 September 2021, with genomic sequencing indicating the Beta variant. However, in October, the patient later revealed that she had tested positive for COVID in January 2021. On 25 November 2021, the patient’s HIV viral load was <50 copies/ml and a PCR test was negative for COVID. While there was no CD4 count performed, suppressed HIV replication and clearance of the SARS-CoV-2 infection suggest her immune system had recovered to some degree.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the samples indicated an ongoing infection instead of re-infections. During the 9 months of infection, the virus acquired at least 10 mutations in the spike glycoprotein and 11 other mutations over and above the lineage-defining mutations for Beta.

The authors consider it unlikely that the novel variant described spread into the general population, and stress that it does not prove that any of the other novel variants originated from an immunocompromised host in this fashion.

Increased vigilance is warranted to benefit affected individuals and prevent the emergence of novel SARS-CoV-2 variants. They ascribed the detection of the case to good connections between sequencing laboratories, routine diagnostic laboratories and frontline clinicians.

The authors concluded that their experience “reinforces previous reports that effective ART is the key to controlling such events. Once HIV replication is brought under control and immune reconstitution commences, rapid clearance of SARS-CoV-2 is achieved, probably even before full immune reconstitution occurs. This underscores the broader point that gaps in the HIV care cascade need to be closed which will benefit other conditions and public health problems, too, including COVID.”