A New Method to Block Listeria Infections

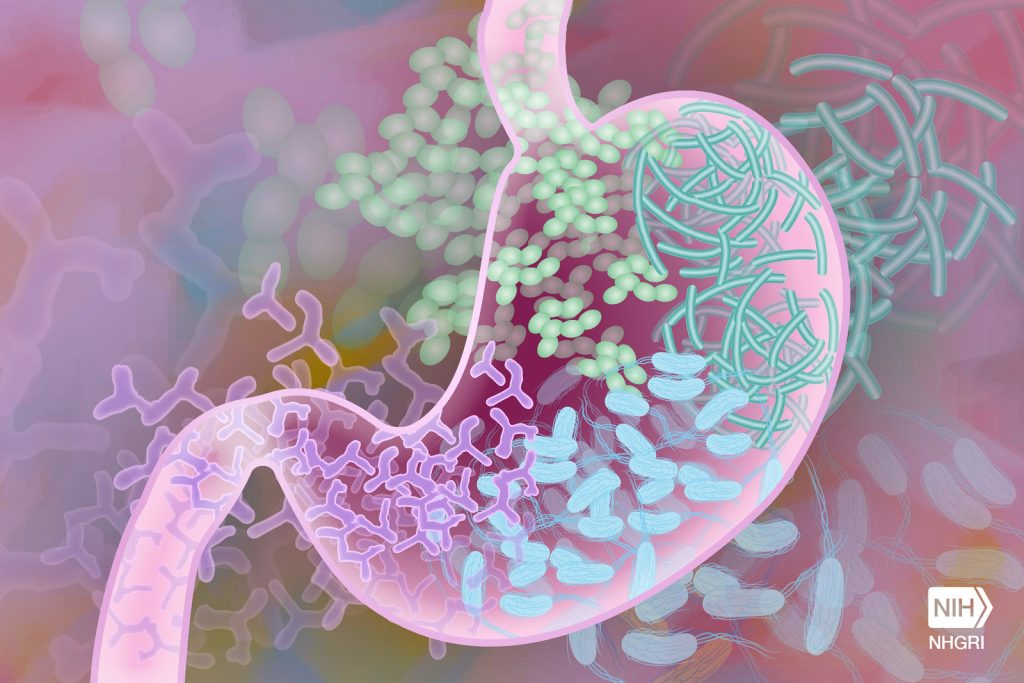

University of Queensland researchers have unlocked a way of fighting Listeria infections, which can cause severe and potentially illness in pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals.

Listeria infection does not cause disease in most people, but can be deadly for the immunocompromised and is also a major health concern during pregnancy and can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth and premature birth.

From 2017 to 2018, South Africa suffered the world’s largest listeriosis outbreak, in which there were 216 deaths out of 1060 recorded cases.

During the study, published in the journal PLOS Pathogens, researchers discovered a way to block Listeria from making the proteins that allow bacteria to survive and multiply in immune cells. University of Queensland’s Professor Antje Blumenthal said using a small, drug-like inhibitor has improved their understanding of Listeria’s weak spot.

“Listeria is found in the soil and sometimes in raw foods. Once ingested it can hide from the immune system and multiply inside immune cells,” Prof Blumenthal said.

“Instead of killing the bacteria, the immune cells are used by the bacteria to multiply and are often killed by Listeria growing inside them.

“Our study showed the bacteria could be cleared with a small drug-like inhibitor that targets the ‘master regulator’ of the proteins that help Listeria grow in immune cells. The inhibitor helped the immune cells survive infection and kill the bacteria.”

Previously, studies into Listeria’s ‘master regulator’, which controls critical proteins that make the bacteria virulent, have mostly been based on engineered bacteria, or mutated versions of these proteins.

“By using a drug-like inhibitor, we were able to use molecular imaging and infections studies to better understand what happens to Listeria when the bacteria cannot effectively grow inside immune cells and hide from immune defence mechanisms,” Prof Blumenthal said.

“We hope that our discovery, together with recent research into the master proteins’ molecular structure and functions, could guide the development of inhibitors and new drugs to treat Listeria infection.”

“Our findings could also inform design of inhibitors against related proteins that are found in different bacteria,” Prof Blumenthal said.

Source: University of Queensland