New research suggests that sepsis can cause alterations in the functioning of defence cells that persist even after the patient is discharged from hospital.

This cellular reprogramming creates a disorder the authors term ‘post-sepsis syndrome’, symptoms of which include frequent reinfections, cardiovascular alterations, cognitive disabilities, declining physical functions, and poor quality of life.This explains why so many patients who survive sepsis die sooner after hospital discharge than patients with other diseases or suffer from post-sepsis syndrome, immunosuppression and chronic inflammation.

The article reviews studies done to investigate cases of septic patients who died up to five years after hospital discharge.

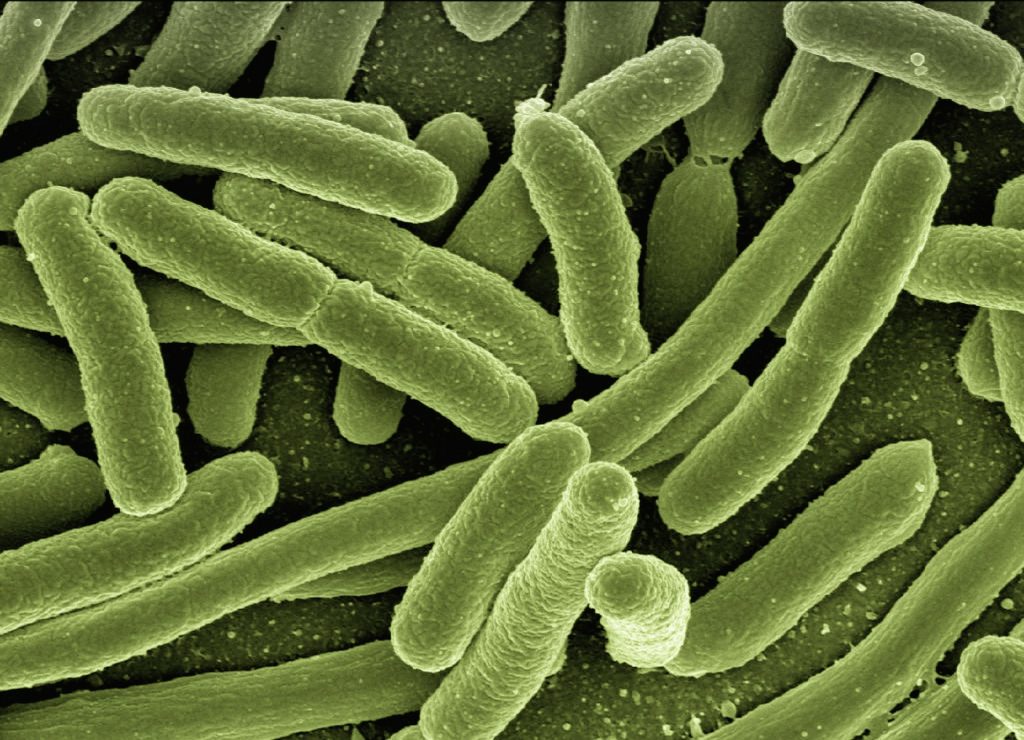

Sepsis is one of the main causes of death in intensive care units, sepsis is a life-threatening systemic organ dysfunction triggered by the body’s dysregulated response to a pathogen, usually a bacterium or fungus. While fighting the pathogen, the defence system injures the body’s own tissues and organs.

If not caught and treated in time, the condition can lead to septic shock and multiple organ failure. Patients with severe COVID and other infectious diseases have an increased risk of developing and dying from sepsis.

Worldwide, new sepsis cases are estimated to reach some 49 million per year. Hospital mortality from septic shock exceeds 40% globally, up to 55% in Brazil, according to the Sepsis Prevalence Assessment Database (SPREAD) study, conducted with support from FAPESP.

“The massive infection and the accompanying intense immune response with a cytokine outpouring during sepsis may promote irreversible cell metabolic reprogramming. Cell reprogramming is unlikely to occur in leukocytes or bone marrow only. This might happen in several tissues and cells that prompt systemic organ dysfunctions […] Bacteria can transfer genetic material to host cell DNA as eukaryotic cells develop tools to protect themselves against the microorganism invasion. The latter may induce cell biology and metabolic reprogramming that remains even after the infection’s elimination,” the investigators wrote in the article.

According to Raquel Bragante Gritte, joint first author with Talita Souza-Siqueira, one of the hypotheses was that metabolic reprogramming begins in the bone marrow, whose cells acquire a pro-inflammatory profile.

“Our analysis of blood samples from patients even three years after ICU discharge showed that monocytes [a type of defense cell] were activated and ready for battle. They should have been neutral. Monocytes are normally activated only when they are ‘recruited’ to the tissue,” Gritte told Agência FAPESP. Both Gritte and Souza-Siqueira are researchers at Cruzeiro do Sul University (UNICSUL) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil.

The researchers conducted a follow-up study of 62 patients for three years after discharge from the ICU at USP’s University Hospital, analysing alterations in monocytes, neutrophils and lymphocytes, as well as microRNAs, in order to identify prognostic markers and factors associated with post-sepsis syndrome.

“Our hypothesis is that white blood cells conserve a memory of sepsis, which helps explain why patients remain sick after they leave hospital,” said co-author Rui Curi, Professor at UNICSUL, and Director of Butantan Institute.

The investigators suggest that sepsis may create a specific macrophage phenotype that stays active even after hospital discharge. “Cell metabolism reprogramming is also involved in the functions and even generation of the different lymphocyte subsets. Several stimuli and conditions change lymphocyte metabolism, including microenvironment nutrient availability,” they wrote.

The next stage of research will be bone marrow studies to understand how cells are reprogrammed by sepsis. “We think the key to this alteration is in bone marrow,” she said. “However, another possibility is that activation occurs in the blood. We’ll need to do more in-depth research to find answers.”

Source: News-Medical.Net